'I grew up reading men, but now I only read women'

It's early 1967, and an unnamed town in northern Mexico receives news that in less than a year, water will repopulate the land, turning it into a dam. Violeta resists the idea of leaving the place where her dead are buried and refuses any financial compensation to leave her home for another place.

Faced with pressure, the resigned accept the money and leave with their clothes, pots, and other belongings, heading for a new destination. They leave behind their homes, which become corpses. Among those who stay are those who yearn for a better economic deal with the authorities, those with unfinished business from the past that prevents them from thinking about a future, those who want to wait until the water reaches their ankles, and Lina, a new arrival who arrives in town with nothing in her pockets. Violeta extends a helping hand, which, in essence, is a maternal hand.

During the eviction period, Violeta witnesses the violence in a town where nothing had happened, and in a matter of a year, she experiences it all: arbitrary state decisions, a femicide, revenge for death, condemnation to nature, dispossession, and suffocation. "Nosotras" is a portrait of the empty promises that development brings to a dusty and forgotten place.

Suzette Celaya Aguilar places women at the center of this story, as defenders of the land and nature, in a society that understands no other form of violence than violence. With her own style, informed by the reading of other authors, "Nosotras" also evokes, if you will, a magical realism, which is more realism than magic.

EL TIEMPO spoke with the Mexican writer and journalist, who was at the Bogotá International Book Fair promoting her debut novel, which is coming to Colombia with the help of Hachette publishing house.

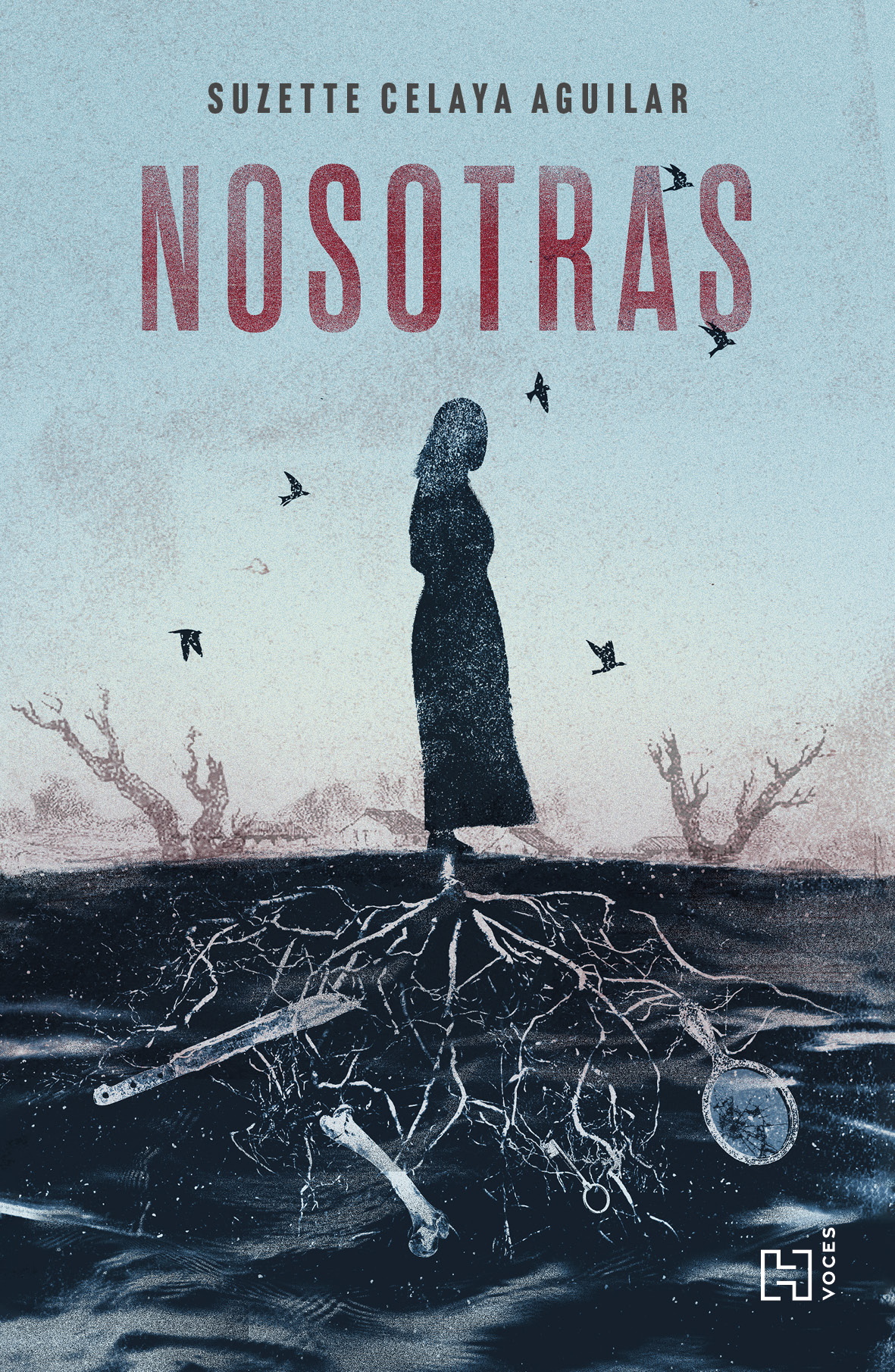

Cover of the novel 'Nosotras'. Photo: Hachette

What authors and styles do you read?

Lately, and without any intention of excluding them, I've been reading only women. One leads you to the other until you can't stop. I really like reading stories set in rural areas. And one author I think of is Selva Almada. She writes stories that seem sordid or in peripheral settings, far from large urban centers, where we think nothing happens, but very profound things happen, where marginal and peripheral characters live. I also like stories with a social charge, and with this, I'm not hoping that all literature has to be like that. Linking her to a contemporary writer, Mariana Enríquez comes to mind. In her horror stories, we always find a social charge. I love how she manages to blend the two. And, finally, I'm reading a lot of everything that has to do with motherhood. Ariana Harwix is a writer who fascinates me because she addresses extreme motherhood, far from the archetype of the good, caring, and loving mother.

I asked you that question because while reading "Nosotras" I noticed hints of magical realism. Were you inspired by that genre, or by any author? Although the female authors of the boom were largely overlooked...

When I started writing this, I never said, "I want it to sound like this," "I want it to belong here," or "I want this to be said about my story." I'm 42 years old, and of course I grew up reading mostly men. And in 2009, 15 years ago, when I studied Creative Writing, most of the authors I read were also men. I can tell you, for example, that writers like Elena Garro and María Luisa Bombal were important readings. In Nosotras , there may be some magical realism, but nothing magical happens in the story. I like to play with ambiguity and give the reader a certain freedom or space to decide what they believe. In book clubs, the character of Isidra comes up a lot, the woman who seems to never stop burning. But that could have been a trick of the children. The reader can think whatever they want. And that's the game I propose. I like to play with reality. Samanta Schweblin also does this a lot, leaving many question marks. And playing with ambiguity can lead to currents like magical realism.

In 'Nosotras', there may be some magical realism, but nothing magical happens in the story. I like to play with ambiguity and give the reader a certain freedom or space to decide what they believe.

Mexican writer and screenwriter Guillermo Arriaga said that you could very well be the heir of Juan Rulfo. What do you think about that? Do you think it's better to be told that you're the heir of Elena Garro or Rosario Castellanos?

It's not true. It's something I find very strong to say. It was a bit of a pressure to be linked to this great figure because I'm just starting out. I don't know if my next novel will be about this feeling, this color, and this mood. The doubt is always there, as is imposter syndrome. I try not to think too much about that comparison or what Guillermo said. I'm grateful for the words and encouragement he's sent me, which, personally, have made me feel like I'm on the right path. He was a judge in the Amazon contest, where my story won.

The title of the book suggests, from the outset, that the protagonists are women. And I'd like to talk about women as figures of resistance, which is the position they find themselves in.

This story was born between 2013 and 2014. Before I started reading exclusively women, I remember doing several voice tests and starting with the idea of a male character, but I felt very uncomfortable. So I switched to a female character. And the story flowed as if you were pushing it along a smooth road. How I felt radically changed, and the story began to flow. Everything seemed more organic to me. Women have had a great responsibility in many processes of maintaining a territory and a community, but they have been made invisible. For example, I live in a border area with the US, and it's normal to see men leaving to make dollars, while women stay behind to support a home. When I study more about forced displacement in my region, I find that women have been the great defenders of water and land, and they have always been on the warpath. Although the story takes place in 1967, it could be replicated in 2025 because the violence remains the same. The only thing that has changed is the social organization and the greater visibility of these struggles. We have developed other forms of resistance. And women continue to defend the land, water, and resources because they are the ones who know best what to do with them, how to manage and care for them.

Celaya Aguilar holds a master's degree in Social Sciences and studies in Creative Writing. Photo: Joel Garcia

It talks about violence, and in "Nosotras" many forms of violence are evident. Perhaps the only one that doesn't appear is drug-related violence, but I don't know if that type of violence was already present in Mexico in 1967...

The theme of violence, along with women, water, and death, was one of the main themes I was interested in narrating. I considered the drug trade at some point, but, just as the town doesn't have a name, I didn't want the story to be tied to a territory and to a northern literature, a narco literature. I wanted to distance myself from that. So I began to develop different types of violence: toward the character, the town, the dead... The story takes place in 1967, but, as I said, it could also take place in 2025, because state violence, male-on-female and female-on-female violence continue. Regarding the latter, I didn't want a story in which men were the only ones exercising violence, because I believe women also exercise violence. I wanted human characters, with setbacks, mistakes, self-deceptions, and lies.

He not only humanized his characters, but also the objects. He writes about corpse houses. What's the purpose of giving them that connotation of living beings in the process of eviction?

For the same reason that water is a central theme, I didn't want to center the story solely on people. When people are placed at the center, it affects other presences, namely, nature. That's why I wanted to consciously name other existences, such as the tree, the earth, the river, the soil in the cemetery...

When people put themselves in the center it affects other presences, that is, nature

Water should be a concern for all of humanity, but in your case, is there anything in particular that prompted you to put it at the center?

I come from a context of severe water scarcity. In Sonora, we have a major problem with water availability, with how it's distributed and used, which are two distinct issues. I think this could be the starting point for this reflection on the centrality of water, because it's a problem I grew up with. Water will continue to be a topic in the projects being developed because it's a major problem and will be an issue for certain regions.

Does the book's ending reaffirm the protagonist's identity and attachment to her town, which she doesn't want to abandon?

I was very clear about how the story would begin and end. I didn't know how it would develop. I wanted Violeta to end up rooted, and that allowed me to play with the figures of trees and roots throughout the story. It also allowed me to ensure that the ending didn't feel forced, but rather felt like the only possible ending for her.

Towards the end, the protagonist's reasons for not wanting to leave the town become clearer. This introduces a topic that, in times of eviction, very few would stop to think about. What happens to the dead in the face of forced displacement? Are they condemned to a double death?

The issue of displacement, whether due to war or a development project, forces you to leave behind many things you can't take with you, like your dead. I find it hard that an eviction takes you away from where your loved ones are buried. And for many people, those spaces where the remains rest are important. And going even further, it's women who reclaim their importance. I think, for example, of the mothers searching for the disappeared in Mexico or the grandmothers in Argentina.

I want to talk about the relationship between Violeta and Lina, who at one point seemed antagonistic, but end up as sisters.

Curiously, Lina is a character I don't get asked about much, or who doesn't usually come up in conversations. Lina, in some ways, is an antagonist to Violeta because she does the exact opposite. With both of them, I wanted to show how the same event is experienced in different ways, each very valid as long as one is satisfied and confident in the decisions one is making. But Lina also allows Violeta to exercise a certain degree of motherhood, after she couldn't do so with her daughter. That's what I wanted.

The story also features a journalist who is more interested in the story of Isidra, the woman on fire who keeps burning, than in the evacuation of a town to flood it. With this character, do you criticize current journalism, the kind that prioritizes clicks over other, more important things?

Not to the practice of journalism as such. But to the belief that since the town wasn't a large urban center, it didn't matter. I'm a communicator, and I recognize that we have a lot of responsibility for what we choose to communicate and how we do it. An event like the one described in the book can have many interpretations. And the work of a journalist in a case like this is essential to raising awareness and providing unbiased information. The journalist also ended up being a witness to what happened, the one who created a memory about it.

eltiempo