Anna Weyant's meteoric rise makes a stop at the Thyssen Museum with her first monograph in a museum.

Anna Weyant has been on a meteoric rise in the art world for five years. Her first sale was a few drawings, displayed on a beach towel at a Hamptons art fair in 2019, for around $400 each (€342). That same year, at the age of 24, she opened her first solo exhibition at 56 Henry Gallery in New York, where each piece sold for between €1,700 and €10,000. The following year, Sotheby's auctioned her work for $1.6 million (€1.37 million), and shortly after, Christie's sold it for $1.5 million (€1.28 million). Three years ago she became the youngest artist to sign with the mega-gallery Gagosian , one of the most prestigious and powerful in the world, and since then her work has continued to be highly valued, with the particular approval of the world of entertainment and Hollywood - she also made a portrait of the model Kaia Gerber for a Vogue cover last year.

So much so that she, often described as an enigmatic personality, has become an art celebrity. Within this dazzling and thriving career, the Canadian artist now arrives at the Thyssen Museum in Madrid for her first solo exhibition in a museum.

“It's worth going beyond the hype , the fashion phenomenon, the artist's rise, because I believe she's an artist destined to last, who has talent, very important qualities, and who, although she is rigorously contemporary because she has a feminist, ironic perspective and a dark humor that is very much of today, has the qualities of an old master,” said Guillermo Solana, the museum's artistic director and also curator of the exhibition, at the presentation on Monday. The exhibition, presented in collaboration with Weyant herself and with the support of Gagosian, ends up being a small retrospective of the artist—like her career itself—with 26 paintings that trace her artistic development.

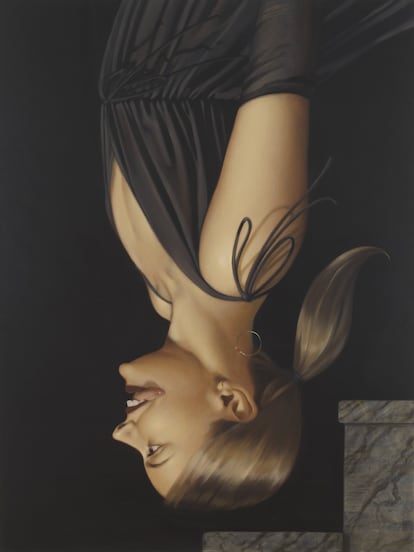

The works almost all feature women between childhood and adulthood, with erotic overtones and, says Solana, "in typical adolescent situations." "It's a period that the artist describes as a very traumatic, very dramatic, but also very comical and very ridiculous time. It's full of tragedies that can also be grotesque comedies."

This duality shines through in the works. In some, it appears more explicitly with the appearance of the doppelgänger figure, a duplication of a figure with a nuance, "which usually represents a social mask," says Solana. There is also a very precise realism in the linework, but at the same time marked by an unreal atmosphere. In this, and in the female protagonist, the curator finds a " deep kinship with Balthus ." "In his figures of young girls, there is a touch of eroticism, sometimes very evident." But, unlike the French artist's voyeuristic male gaze, Weyman, Solana assures, "does it as if with an attempt at contestation. His presentation of eroticism in the figures of young girls is somewhat disturbing or unsettling. This is not the way to present an object attractive to the male gaze."

The reference to Balthus's work is not the only one that emerges in Weyant's work. There is a wealth of artistic references, ranging from the Baroque to the art of the first half of the 20th century. So much so that in the exhibition, the artist shares walls with five paintings from the museum's permanent collection, including Balthus himself, but also Mattia Preti and René Magritte , which are intended to exemplify these connections. The artist herself, who was not present at the event, acknowledged this in a message read by a representative: "Having my paintings in dialogue with artists like Magritte and Balthus from the museum's permanent collection is exciting for me. These are artists who have had a significant influence on my own practice."

Her enigmatic and reserved personality is ultimately reflected in a work full of ambiguities. Her characters seem to live in a kind of fairy tale that orbits between parody and collapse where, says Solana, "the first impression can be misleading." There are half-inflated balloons, undone ribbons, or almost wilted flowers, and it's difficult to understand, for example, whether the screams coming out of some of her women's mouths are of terror or ecstasy: "She also sometimes hides expression, hiding it or turning it upside down. All of this generates a disturbing, ambiguous, and sinister sensation, captured with an immaculate fidelity to reality."

The final part of the exhibition is dedicated to a series of still lifes, much less popular, but, according to the Thyssen's artistic director, "absolutely dazzling in their workmanship." "It was the part that made us discover them the most. They contain as much malicious intent, ambiguity, and threat as the portraits."

Part of the mystery that radiates from her work stems from her own personality, according to Bernard Lagrange, art advisor at the Gagosian Gallery, which is also a reason for her success: “She’s a very reserved person; she loves being alone painting. Whenever she’s forced to leave her studio and interact, she’s aware of what it means to present yourself by creating a mask or a kind of double, which I think is something many people, especially young people, can relate to. She’s created work that is mysterious, enigmatic, and speaks to all generations. It’s also technically very admirable, making the work easy to understand at first glance.”

EL PAÍS

%3Aformat(jpg)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fbae%2Feea%2Ffde%2Fbaeeeafde1b3229287b0c008f7602058.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2F93c%2F97d%2Fe97%2F93c97de973cf7c7473574b683cae5045.jpg&w=3840&q=100)

%3Aformat(jpg)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fbae%2Feea%2Ffde%2Fbaeeeafde1b3229287b0c008f7602058.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2F009%2F345%2F81d%2F00934581d2b64f0189f7fbc623cb9d5d.jpg&w=3840&q=100)