An earthquake like the one in Torrevieja in 1829 would cause thousands of deaths due to overcrowding in tourism.

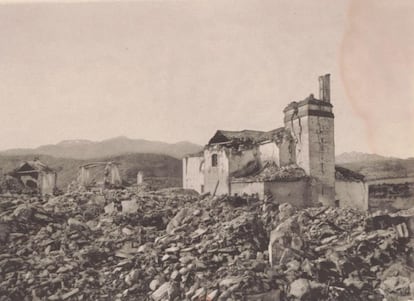

On Christmas Day in 1884, the earth shook for a long 20 seconds. Many clocks stopped at the hour of the catastrophe, around 9 p.m. In the city of Málaga, thousands of people fled in terror from theaters and cafes. But the worst was happening in about 100 inland mountain villages. Arenas del Rey, located on sandy soil, completely collapsed, along with its 400 houses. Most families were at home having dinner and celebrating a holiday. That day, about 900 people died, and another 2,000 were injured. It was the last major earthquake in Spain's history, and the first to spark an unprecedented international aid campaign for the victims, who lived months of terror due to frequent aftershocks. More than 140 years later, scientists are certain that an earthquake like this will happen again sooner or later, although it is impossible to know when.

A team of geologists has analyzed the impact of a similar earthquake today. In addition to the Arenas del Rey earthquake, they also observed the Torrevieja earthquake of 1829, which killed nearly 400 people and forced the relocation of five entire towns—Guardamar, Torrevieja, Almoradí, Rojales, and Benejúzar .

The current estimates are chilling. The area affected by the Torrevieja earthquake is now one of the most populated tourist destinations in the country. In these areas, the permanent population has increased sixfold, and occupancy increases several times more during peak tourist seasons. Based on the current population of this area, according to data from the National Institute of Statistics in 2024, an earthquake like the one in the 19th century would leave around 5,000 dead with a 60% probability. In the summer, the figure could reach 11,000. Economic losses would be around €100 billion.

"We are aware that these estimates are terrifying, but we have been very careful in applying the models and have always taken the most conservative ones," explains Javier Élez, a researcher at the University of Salamanca and first author of the study.

These calculations were developed using the tool used by the United States Geological Survey to estimate the impact of severe earthquakes worldwide based on their intensity. The system is called PAGER , which stands for Rapid Earthquake Impact Estimation for Rapid Response. Spanish scientists have modified it to include updated population data and the geological characteristics of Spain. The system, which also uses satellite imagery, allows for an initial assessment in a matter of minutes.

“Earthquake estimation always works with probabilities,” explains Pablo Silva , professor of Geological Risks at the University of Salamanca and co-author of the work, which is published in the specialized journal Natural Hazards . “ If you ask me if these earthquakes will happen again in a few years, the risk is low. But if we consider 250 years, the probability would be almost 100%,” he warns. This tool can serve “to prepare for catastrophes that we know will happen again, and to be able to react better to them,” he argues .

In the Torrevieja earthquake, it was very difficult to rescue the population because all the wooden bridges over the Segura River collapsed, leaving the southern bank cut off. "In a modern earthquake, it's crucial for emergency services to know which access and evacuation routes would be available based on the geological characteristics of the terrain," Silva adds. "Urban expansion and the rampant tourism development in the southern part of Alicante increase the area's vulnerability to extreme geological events by 400%," the scientist warns.

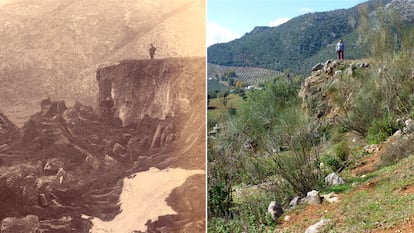

“In the Arenas del Rey earthquake, entire farmhouses moved 200 meters due to landslides,” explains Miguel Ángel Rodríguez-Pascua , a geologist at the Spanish Geological and Mining Institute (IGME-CSIC), co-author of the paper. It was one of the few historic earthquakes that left scars—landslides, cracks—that are still visible today. “These sites are part of our national geological heritage, and they can also be the perfect place to train emergency units,” he explains. In the Torrevieja earthquake, liquefaction occurred: a seismic phenomenon in which the ground literally dissolves and can swallow buildings with all their occupants inside.

The two cases studied are in the area of greatest seismic activity in Spain. All of the scenarios analyzed would require international assistance, and many of them would result in human and economic losses for which the country is "not prepared," the report warns.

Rodríguez-Pascua and other IGME scientists are part of the Geological Emergency Response Unit, which has collaborated with the Military Emergency Unit in disasters such as the La Palma volcano eruption and the Valencian disaster . The scientists prepared seismic scenarios for two earthquake simulations in Seville (2016) and Murcia (2018), with a magnitude of 6.5, similar to that of the Arenas del Rey and Torrevieja earthquakes. The team has been developing tools adapted to the geological and geodynamic characteristics of the Iberian Peninsula since 2012 thanks to funding from theMinistry of Science, Innovation and Universities .

The authors believe that Spain lives "with a false sense of security" regarding seismic risk. This is because there have been few serious earthquakes in historical periods. The last significant one was the Lorca earthquake in 2011, which measured 5.2 magnitude and caused nine deaths, 300 injuries, and losses of approximately €500 million. There is a whole branch of seismology that seeks archaeological traces of prehistoric earthquakes to broaden the statistical picture and gain a better idea of what may come.

Part of the scientific team collaborated on the National Plan for Monitoring Seismic, Volcanological, and Other Geophysical Phenomena recently approved by the Government. The plan was directed by the National Geographic Institute (IGN), the entity responsible for studying and monitoring seismic risk in Spain and dependent on the Ministry of Mobility and Transport. The document proposes 58 measures to strengthen surveillance and detection networks for destructive natural phenomena, such as earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, tsunamis, and solar storms. The IGME scientists proposed creating a map of all the country's active faults , explains Rodríguez-Pascua. With this map, PAGER could be used to estimate risk for specific locations.

“It's undoubtedly a useful tool that can give a very good idea of the range of casualties and economic losses faced,” says Juan Vicente Cantavella, head of the National Seismic Network at the IGN. The geophysicist holds this view despite the model's limitations, which are primarily the lack of statistics on major earthquakes in Spain, due to their scarcity. Also lacking is detailed data on the characteristics of buildings in each area, which is essential for estimating the real risk, since a village of adobe houses is not the same as a village of concrete houses. The IGN produces seismic risk maps based on records of past earthquakes. “In any calculation,” explains Cantavella, “even if there is a low probability of a major earthquake in, say, 50 years, there is always an assumed risk.” In any case, he believes that the PAGER, adapted to the specificities of Spain, “is a certainly useful tool.”

"This is a necessary, interesting, and well-conducted study," says Álvaro González , a geologist specializing in earthquakes at the Barcelona Center for Mathematical Research. "The serious human and economic losses estimated by this study are unfortunately reasonable and demonstrate the importance of being prepared for similar events," the researcher adds.

Twenty years ago, using less precise techniques, González already estimated the significant human losses if earthquakes of the magnitude of those in Torrevieja or Arenas del Rey were to occur again. "This type of research is necessary to give us an idea of the possible consequences and to raise awareness of the need to be more resilient to these events: where buildings should be rehabilitated to make them more resistant, what resources should be prepared for emergencies, how to educate the population on how to protect themselves, and what financial resources should be available for relief and reconstruction. Large earthquakes, due to their fortunate rarity, are gradually fading from the collective memory, and it is necessary to warn that the threat of another destructive earthquake remains, and it is only a matter of time before another one occurs," he adds.

In 2013, González drew attention to this problem in a letter to the editor of EL PAÍS , discussing the earthquake that destroyed Lisbon in 1755 and killed thousands of people in Spain and Portugal. “The survival and well-being of future generations in Spain will depend on how well we are able to research, prevent, and educate about natural hazards today,” he wrote.

Estimates for a current earthquake similar to the one in Arenas del Rey provide another side of the coin. None of the possible scenarios show human losses close to those recorded in 1884, 141 years ago. One explanation is the depopulation suffered in the Granada mountain ranges, explains Salamanca professor Pablo Silva. The other is that the earthquake struck just when almost everyone was at home.

EL PAÍS

%3Aformat(jpg)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fbae%2Feea%2Ffde%2Fbaeeeafde1b3229287b0c008f7602058.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2Ff95%2Ff80%2F242%2Ff95f8024262ae023bb2558cc9dbbc7cf.jpg&w=3840&q=100)