<em>Jeopardy!</em> 's Most Infamous Moment Haunted the Show's Fans, Its Stars, and Even Alex Trebek. It's Clear Why Now.

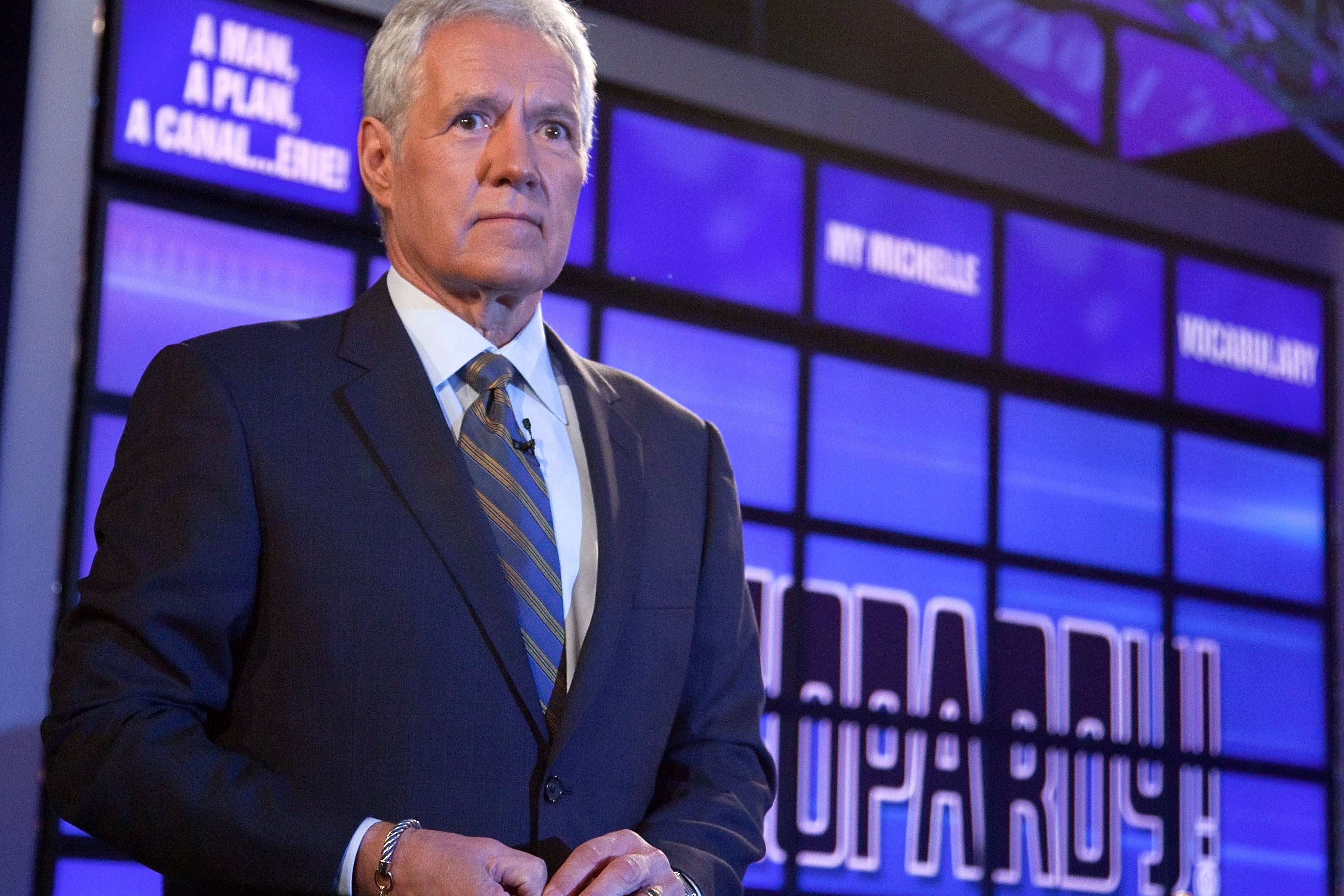

One morning in 2010, Alex Trebek walked onto the IBM campus not far outside New York City and prepared to inspect what would become the most unusual player in Jeopardy! 's history.

The trip, clear across the country from the show's Culver City set, had been carefully planned. David Ferrucci, a computer scientist at IBM, had spent years leading a team to develop what would become the first and, so far, last nonhuman ever to compete on Jeopardy! Longtime host Trebek would watch three practice games played with “Watson,” as the system was named, and two human contestants. Then the Jeopardy! team would be taken to lunch nearby, and Trebek would ultimately take the stage and host two more Watson practice games himself.

By then the preparations for a future televised Jeopardy! contest with IBM's creation were well underway, but this was the first time Trebek would encounter the technology in person, and his approval was crucial. Ferrucci was eager to show off one element in particular: the display, which had been rigged to show Watson's top three guesses whenever it answered, along with the numerical confidence rate it had in each one. For Ferrucci, this feature was central to demonstrating the computer's language-processing capabilities, because it showed that Watson wasn't just spitting out answers—it was reasoning. If Watson were ever going to be deployed to industries like health care, its human users wouldn't just want to know its best guess. It would be infinitely more valuable to know if Watson was 95 percent confident or just 30 percent, and whether those confidence levels were in line with its actual accuracy rate.

It also made for better viewing. Ferrucci had brought his young daughter to the lab earlier in the process and showed her Watson as it played against human opponents. When Watson declined to ring in, Ferrucci's daughter turned to him and asked if the computer had crashed. He struggled to explain that it hadn't—it just wasn't confident enough to hazard a guess. At Ferrucci's urging, IBM's marketing team commissioned a survey that confirmed what he suspected: If people couldn't see Watson's weighted guesses, the competition was boring and difficult to understand.

By the time Trebek arrived at IBM, the Watson team had already sold Jeopardy! producers on the idea of the display, and the answer panel popped up every time the computer offered a response. Initially, sitting with Trebek in the greenroom, Ferrucci was excited: Trebek liked the new addition. “He's watching the answer panel, and he says, 'That's fascinating,' ” Ferrucci remembered.

He then told Trebek that they were going to include it in the televised episodes.

“He goes, 'Oh, no, no. No, we're not,' ” Ferrucci said. “ 'Because then it's not Jeopardy! ' ”

“ Jeopardy! is about its design,” he said Trebek told him. “You have the headshot, you have the question shot, you have the answer shot, you have the two-people shot, you have the three-people shot.”

“He knew every shot, every angle that's played out to make a Jeopardy! game,” Ferrucci said. “And he knew what the audience was supposed to be doing during that shot.

“He said to me, 'When that answer panel is up, I'm doing something completely different. This is not Jeopardy! ' And what he meant by 'It's not Jeopardy! ' is 'The audience is having a completely different experience now.' ”

IBM was strongly motivated to show what the computer was actually doing, but Trebek wasn't playing ball. At lunch, Ferrucci and others from the IBM team tried to convince him. Even Harry Friedman, then the show's executive producer, got involved. “Harry explained to him why it was important,” Ferrucci said. “And he said, 'No, I'm not doing it.' ”

The moment was telling of the solemn protector role that Trebek, who died in 2020, played on Jeopardy! —and also of the widespread uneasiness with the computer invader in an otherwise very familiar, very human milieu.

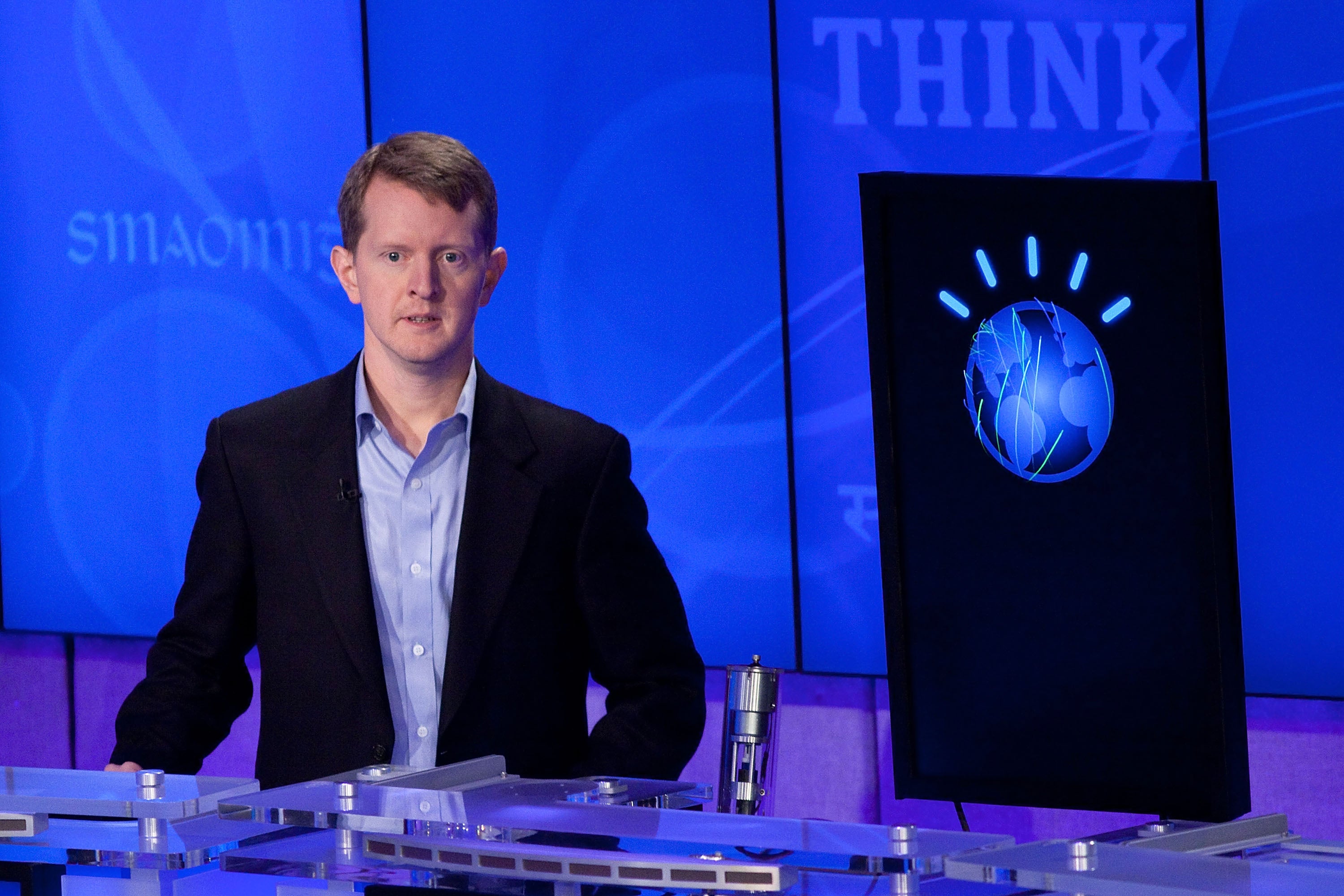

Watson famously did make it onto the air in 2011, playing against current host Ken Jennings and Brad Rutter. The episodes were a ratings bonanza and a media spectacle, garnering everything from a New York Times Magazine cover to a PBS documentary. It was a cutting-edge computer-science gamble and the vanguard of the modern age of artificial intelligence, a comparatively wholesome amuse-bouche to the current slate of LLMs and AI slop. And it remains something that Jeopardy! diehards fervently debated to this day.

Indeed, in the years since the Watson games, hating on the computer—or at least hating on its nonsentient claims of victory—has become a favorite cause among Jeopardy! devotees. “Of course Watson kicked the humans' butts—it wasn't a fair fight,” wrote one contestant after the games aired. In 2021 Jordan Boyd-Graber, a computer science professor and show alum, released a lecture professing that the Watson games were rigged. The subject is a perennial favorite on the Jeopardy! subreddit, where the games have been dismissed as “ disappointing ,” “ unfair ,” and—my favorite—“a gimmick” that introduced “the only [contestant] I genuinely hated .”

James Holzhauer, the series superstar who made his Jeopardy! debut nearly a decade after the Watson slugfest, is just as pointed. “The Jeopardy! match with Watson was essentially rigged due to the computer's superhuman reaction time,” he said.

The anger is especially acute among some of those who faced Watson. “It was blindingly obvious to me that what was going on was not a fair fight,” said David Madden, a 19-day Jeopardy! champion who played Watson while the system was being tested. “What made it so infuriating was that this was turned into a sleight-of-hand exercise.”

Despite coming around to the event, Jennings told me Trebek went on to have misgivings of his own. “Audiences would often ask him about Watson, and you could tell that he was still kind of prickly about it after all this time,” Jennings said. "People would ask him who his favorite Jeopardy! player was, and of course he would never commit to that. He would just say, 'Anybody except Watson. Boy, I hated that Watson.' ”

Now, in a very different moment for both Jeopardy! —its 42nd season begins Monday—and the public's relationship with AI, it's worth asking: What was the Watson showdown? Among other things, it was a prime-time preview of the anxious, angry moment we're in now.

Ferrucci's first thought on hearing about a plan to build a computer that could compete on Jeopardy! was: absolutely not.

At the time, he worked within IBM's research arm, where he focused on natural language processing in AI The Jeopardy! idea had been floating around IBM as a new spin on Deep Blue, the company's chess computer, which took down Garry Kasparov in 1997 .

By the mid-aughts, an IBM executive named Paul Horn had brought the pitch to the research department twice already. If you're trying to prove your technology is powerful and intelligent in front of the largest audience you can, you could scarcely come up with a better stage than Jeopardy! , the quiz show that has long served as a pop-culture byword for smarts. “People associated it with intelligence,” Horn said at the time, and he wanted that platform.

But Horn had been rebuffed. Ferrucci was well aware of the technology's limitations: The best language-processing models back then were hitting as high as 35 percent accuracy, he told me. “Even there, the questions were simpler than Jeopardy!, because they were very straightforward,” he said. “To win at Jeopardy!, you had to have accuracy in the 80-to-90-percent level. That is nowhere near what machines could do.”

So in 2006, when Horn made the rounds for a third time, Ferrucci was intrigued, but only so much, given the extreme challenges. “A group got together to figure out how to tell poor Paul Horn, for the third time, no,” Ferrucci said. But as they talked with him, Ferrucci started to wonder: Could it be done? “It went from 'This is completely impossible' to 'Oh my God, this is easy' to 'OK, it's possible but very hard.' They said to me, 'OK, Dave, well, it's on you.' ”

The next year, IBM approached Jeopardy! Ferrucci, who had officially signed on as the head of the Watson project, and two members of IBM's marketing staff flew to Los Angeles, where they met with Friedman and Rocky Schmidt, another longtime producer, and toured Jeopardy! 's together. But for the computer scientist, explaining the idea was easier said than done. “It seemed like a very nice meeting,” Ferrucci said. “But what we learned later was they had no idea what we were talking about.” Eventually, Ferrucci found out that Jeopardy! had been mystified: Apparently, the show was under the impression that IBM had simply been attempting to get an IT contract with Sony, which produces the program.

The show's top brass weren't the only ones initially confused by the pitch. Ferrucci remembers a senior executive at IBM “with a lot of influence” who was brilliant but didn't watch television. The executive met with Ferrucci's team, incensed that the group had gotten funding for the project—his wife, he told Ferrucci, had sat him down to watch a couple of episodes of the show, and he was horrified that IBM would waste its resources there. Eventually, the team figured out that the executive hadn't been shown Jeopardy! He'd watched Name That Tune .

IBM's first attempts to get the computer that would become Watson to play Jeopardy! weren't encouraging: The computer was getting just 13 percent of clues from recent shows correct. “Thirteen—not 30,” Ferrucci said. Its confidence estimation—a crucial part of the AI, as it would tell the computer whether to ring in—was even worse.

Soon, IBM began hosting practice games with Watson at its Westchester County research campus hosted by the actor Todd Alan Crain, first against IBM employees pulled in during their lunch breaks and, eventually, against Jeopardy! champions handpicked by the show who were ushered in under the strictest confidence. Some of the early iterations were not exactly showbiz-ready: Crain remembers one version where Watson, whose enormous “body” of servers—“10 refrigerator-sized units” in a chilled room, per Crain—was represented in the room by a speaker crammed into the top of a trash can that was then draped in a black cloth.

“It was very, very low rent,” Crain said. On one such exhibition day, with both Jeopardy! 's and IBM's leadership on hand and the PBS documentary crew filming, Watson responded to a prompt asking for the German word for “no”— nein —with a bit of creativity that likely wouldn't be well received during your grandmother's 7 pm game show hour: “fuck.”

“Everyone in the audience lost their minds,” Crain said. “It was chaos in the room. There was sweaty laughter.”

But the computer improved continuously. By the time Friedman and Schmidt visited IBM's headquarters in late 2007, Watson was up to nearly 50 percent accuracy, with its performance ticking ever upward. Once Jeopardy! alumni started coming in, the fields embraced the challenge with the kind of nerdy defensiveness for humankind that you might expect from the trivia elite: Ferrucci recalls that one player turned up in a John Henry T-shirt.

“I was a mom of two tiny kids, and they were willing to put me up in a hotel, and I got to play Jeopardy! again,” said Alison Kolani, a tester who won on Jeopardy! in 2008. “So I was like, 'Whatever you want me to do, I will do.' ”

To this day, the players who managed to steal a game or two from Watson remain fiercely proud of the accomplishment. “I started to notice something that you would never, ever, ever see on the show: The human contestants would sort of team up against Watson,” said Crain, who hosted nearly 200 games over the course of 25 months. “So if one of the contestants chose a category that happened to be a Daily Double, the other human contestant would undoubtedly say something like, 'Go get it.' They would encourage the other contestant.”

Not that this occasional bullying did much, given that Watson had no idea what his opponents were up to. But that wasn't the point. “It's not that he or she wanted to win it themselves,” Crain said. “They were hoping that we as humanity would win those games.”

Madden, the 19-day champ, was one of the players who managed to conquer the computer. “I knew going in that I was going to have to play a very different game than what I played when I was on the show,” he said. “I just knew that I was going to have to go for broke.”

So that's what he did, chasing and finding Daily Doubles and making massive wagers that would at the time have been highly unusual on Jeopardy! , nearly a decade before Holzhauer transformed the game . And although he won twice with this strategy, it was in the practice games that the initial hints of an enduring sore spot for fans of the quiz show emerged: Watson was extremely good at ringing in first. “It became very clear very quickly that Watson had just ridiculous buzzer timing,” Madden said.

Kolani—who took to using male pronouns for Watson because of the computer's masculine voice—noticed the same. “It was very fast and almost always right,” she said. “It was humbling.”

The journalist Stephen Baker embedded with IBM over the course of Watson's development and the Jeopardy! project, eventually publishing a book about the initiative called Final Jeopardy: Man vs. Machine and the Quest to Know Everything . At the time, IBM was leery of the phrase artificial intelligence , insisting instead on calling the computer a “question-answering system.” “They didn't want to call it AI because AI had a terrible reputation of false promises,” Baker told me. “They warned me never to call it AI”

In Final Jeopardy , Baker recounts how IBM and Jeopardy! went back and forth over how Watson would buzz in. By its very nature, a computer could ring in much, much faster than even the savviest buzzer fiend. “The electrical journey from brain to finger took humans two hundred milliseconds, about 10 times as long as Watson,” Baker wrote. But IBM found that human players, knowing that the opening to ring in was imminent, could use the anticipation to get a head start with their comparatively sluggish neurons; some “buzzed within single milliseconds of the light” that signals that players can buzz without a lockout penalty.

Yet, as development progressed, Jeopardy! execs grew concerned, eventually demanding that the company build a makeshift finger that, in IBM's estimation, “would slow Watson's response time by eight milliseconds,” according to Final Jeopardy . That left Watson with a buzzer speed of approximately 28 milliseconds to the average human's 200.

Still, it hadn't stopped Madden or any of the other show alumni who managed to defeat the computer. Indeed, Baker himself nearly took down Watson when IBM found itself short a contester and subbed the writer in. Baker led until Final Jeopardy!, he told me, but the computer bet bigger and won. Still, he was proud of the feat and soon after brought about his almost-victory to Ferrucci.

“And he said, 'Oh, yeah, that must have been an old copy on somebody's laptop,' ” Baker said. “It was totally out-of-date software.”

Jennings and Rutter were intentionally kept away from Watson and IBM in the years leading up to the match.

It hadn't taken much to persuade either man to sign on. Jennings remembers getting a call from the show years before the games would eventually tape asking him if he remembered Deep Blue. “'IBM thinks Jeopardy! is the next frontier after chess,'” Jennings said he was told. “ 'If they could ever get an algorithm up to speed, would you be one of the contestants?' And I said sure. I had been a computer science major. I knew that question-answering algorithms were nowhere near Jeopardy!

As the tapping grew closer, and since Watson was deprived of their game stats, Jeopardy! brokered for both contestants to get Blu-ray recordings of some of the computer's practice games against other Jeopardy! disputants.

“That's how I got my first Blu-ray,” Jennings said. “They mailed me a Blu-ray so I could watch Watson cream '90s- and 2000s-era Jeopardy! champions.” And cream it did, much to his initial surprise: “It was clearly playing as well or better than Jeopardy! opponents I would have been very scared to play,” he said.

Particularly discomfiting for Jennings was what came with the recording of the practice games: an early draft of an IBM research paper that, among other things, featured a scatter plot of Watson's performance getting closer and closer to what the researchers—and Ferrucci, the paper's lead author—called the “winners' cloud.”

“Why are there two colors of dot in the scatter cloud?” Jennings remembers wondering—and then making a starting discovery. His 74 wins back in 2004 weren't just the longest streak in Jeopardy! 's history: They were valuable and abundant data about what was required to win, which the IBM team had separated with its own shade on the chart. “One of them is Jeopardy! champs, and the black dots are actually me. I'm the part of the cloud it's trying to get to.”

Still, neither Jennings nor Rutter contemplated strategizing with the other about how to take their shared digital foe down. “The rivalry was still hot,” Rutter said. Rutter at the time was undefeated on the show, having beaten Jennings and a slew of other storied contestants in 2005's Ultimate Tournament of Champions. When Jennings learned that Rutter would also be part of the Watson games, he remembers thinking, “Oh, I have to play Brad again?”

“Not that we never didn't like each other, but we were definitely not as close as we came to be later on,” Rutter said. “I wanted to beat him as badly as I wanted to beat the computer.”

Even still, Jennings told me, there was little they could have done to shake Watson, who couldn't see or hear. “There's nothing his opponents could do in particular in the way Garry Kasparov might have tried some odd opening to throw off a computer chess player,” he said. “There's just less of that kind of strategy in Jeopardy! ”

In the intervening years since their invitation to play a computer, Jennings and Rutter had gone on with their lives on the West Coast. Ferrucci and his team kept working on Watson as its accuracy and confidence rates improved. Jeopardy! alumni continued to cycle through the campus, and fewer and fewer walked away victorious. IBM and Jeopardy! began cranking up their respective PR machines, with reporters eager for a first look at the machine said to be able to take down some of the nation's foremost brainiacs.

And then it was December 2010. With tapping just weeks away, Trebek made his fateful visit to the IBM campus and instantly shot down the display showing Watson's confidence level. A crucial part of Ferrucci and IBM's vision was out—at least for the moment.

Defeated, the group made its way back to IBM's office to prepare for the two Watson games that Trebek would host. Then Ferrucci had an idea: They'd switch the answer panel off right then and there. Watching a feed of the first game Trebek hosted from the greenroom, he remembers the host lamenting, several clues in, that Watson's panel was gone.

Then, just as the second game started, Trebek's voice rang out over the auditorium intercom: “Ferrucci!” he cried. “Come in here!”

Jeopardy! contestants have sometimes compared receiving a rebuke from Trebek as akin to being called into the principal's office. This was no different. Ferrucci crossed the hall and entered the room. “Not only do I want the answer panel on a television,” Ferrucci said Trebek told him, “I want it on my podium.”

Finally, it was time to play.

The day before the Watson episodes would tape, Jennings and Rutter traveled to the IBM campus for a round of practice games against the computer. Rutter remembers encountering a traditional opponent, at least in terms of its gameplay. It played categories from the top down and didn't seem to be searching for Daily Doubles. Most notably, neither Jennings nor Rutter remembers having too much trouble beating it on the buzzer. They swiftly joined the ranks of Watson victors: They played three full games, Rutter said, and each contestant, including Watson, won once.

The following day, IBM made a change. In Final Jeopardy , Baker describes how, just before the televised match began, technicians switched Watson to what he called “championship mode.” This, Baker wrote, entailed two changes. First, cluing Watson in to the fact that the match was (ahem) a two-day, total-point affair , which shifted his betting strategy. And, Baker continues, “the IBM team directed the machine to hunt for Daily Doubles.”

As he entered the amphitheater, Jennings remembers, he realized that it was filled in part with IBM board members. “Somehow that had not occurred to me, that this was an economic event,” he said. “Most Jeopardy! games do not affect the financial markets, let's put it that way.”

The first game's initial round seemed to indicate that the two-match duel might not go the computer's way: While Jennings lagged behind with $2,000, Rutter had managed to tie Watson at $5,000. From that point, though, neither man seemed able to do much more than watch as Watson steamrolled his way to victory. Watson had some goofs, most notably when he guessed “Toronto?????” in response to a Final Jeopardy! clue—the computer's Achilles' heel, as Ferrucci's team well knew—that read “Its largest airport is named for a World War II hero; its second largest, for a World War II battle.” (To Ferrucci, who would leave IBM the following year, the whiff wasn't a complete disaster: The question marks indicated a lack of confidence, and had its hard-won answer panel been visible, as it was for no–Final Jeopardy! clues, it would have shown that Watson's second guess was Chicago—the right answer.)

But mostly Watson cruised. Over and over, Jennings and Rutter could be seen banging away at their buzzers, only for the computer to get in first with the right answer. In a break from how it had played in the practice games the day before, Watson zoomed around the board, clearly on the prowl for Daily Doubles. It found them, betting big and strangely: It turned up five of the six opportunities, wagering amounts like $6,435 and $1,246 while both adding to its total and boxing out its human opponents.

Rutter remembers joining Jennings backstage during a break, by which point it was clear that Watson was spurning the top-down gameplay of old and actively seeking Daily Doubles, particularly across the lower runs of the board. “Hunting the Daily Doubles—that actually makes sense,” Rutter said he and Jennings discussed in the wings at IBM.

Lots of Jeopardy! heads would attribute the popularization of that strategy to James Holzhauer, but not Rutter. “As great as James is, he gets a lot of credit for jumping around the board and hunting for Daily Doubles,” said Rutter, who has deployed the strategy himself in subsequent tournaments. “And that's not where I got that. Watson is where I got that.” (Holzhauer did take it mainstream, however: He earned nearly $2.5 million during a 32-game winning streak with the strategy in 2019, and today you can see it in action most nights on Jeopardy! )

The audience at IBM was, unsurprisingly, overwhelmingly pro-Watson, and as the computer's victory looked more and more certain, the crowd made its enthusiasm known in a most un- Jeopardy! way. “They didn't quite know the etiquette,” Jennings said. “The thing that it reminded me of was how pageant moms will always coo over their little darling when they do anything. Watson would get some easy clue right and there would be chatter in the room.”

The humans lost. Watson finished with $77,147 to Jennings' $24,000 and Rutter's $21,600. Famously, Jennings added, “I for one welcome our new robot overlords” to his last Final Jeopardy! response as Rutter bowed to the human-free reader beside them. It was hard to dispute their read: At virtually no point did it seem as if either human had a chance of victory.

But onstage, as applause for a machine without ears rained down, Jennings and Rutter looked more pleasantly gobsmacked than disappointed, a state perhaps helped by their respective $150,000 and $100,000 consolation prizes. “After the whole thing was over, Ken and I went back to the greenroom and I was like, 'Well, I guess that's what it's like to play against us,' ” Rutter said.

After Watson won, Jennings was crowded by IBM engineers and executives who were eager to tell him how valuable his own data had been as they had programmed the computer. “They were like, 'You should feel great. There's a lot of you in Watson,' ” Jennings said. “It didn’t make me feel any better.”

The enduring dispute over the fairness of the Watson games is crystallized in the deployment of championship mode.

That it was enabled only for the televised games drew the criticism of many—including Trebek. Baker spoke with Trebek two days after the Watson showdown, and the host was furious about what he saw as a bait and switch. “I think that was wrong of IBM,” he told Baker. “It really pissed me off.

“IBM didn't need to do that,” Trebek continued. “They probably would have won anyway. But they were scared.”

Both Jennings and Rutter describe being touched when they read what Trebek told Baker next: “I felt bad for the guys, because I felt they had been jobbed just a little.”

“He was so protective of us, and that just spoke volumes about the kind of guy that Alex was,” Rutter said. “He really did believe that the contestants were the stars of the show, not him”—an adage Trebek was fond of repeating. “As wrong as we all know that to be now,” he added.

For Rutter, it's hard to shake the feeling that IBM had Watson intentionally play poorly—or at least not as well as it could—during their practice games. “It was definitely sandbagging,” he said. “The way it played out, especially on the buzzer, was that it was just like you would expect with Ken and me and, let's say, Jerome [Vered],” the third player in the Ultimate Tournament of Champions finals, he said of the three practice games. “There was nothing out of the ordinary about it. It just seemed like another good Jeopardy! player.”

In IBM's view, the practice sessions the day before the televised games hadn't been a chance for Jennings and Rutter to scout Watson's playing style: They were “to test the machinery and the buzzer,” per Baker. And nothing about championship mode should have affected Watson's buzzer timing, according to Baker—both Jennings and Rutter had edged out the computer's blazing signaling device fair and square in their first go-around.

Still, it's hard to know for sure. “From Alex's perspective, it looked like Watson was dumber than it turned out to be,” Baker told me of the practice games. “Like me, they probably played an older version of the software.” Asked if, even with the makeshift finger, Watson's buzzing ability was just too fast, Baker said, “I think in the end it was.”

In Rutter's view, it was the buzzer timing that doomed him and Jennings. “Yes, theoretically, and it did happen sometimes, if Ken and I were right on it, we could get in before Watson if Watson buzzed,” Rutter said. “But the real buzzer thing is speed plus consistency, and it had exact consistency. And there's just no way a human can be that consistent on the timing of it.

“There was no way it could lose,” he said.

Complicating matters, Rutter said, was that both he and Jennings were—at least for humans—very good at winning buzzer battles. “If you have one buzzer monster and two other people, the two other people sort of cannibalize each other,” Rutter said. “It's like, OK, a human can get in front of the computer on this one, but which one is it going to be? If either Ken or I had been really off, then maybe the one who was on would have a chance, but with both of us playing, well, there was just no way.”

Whatever his quibbles over the buzzer, though, Rutter looks back on the episode fondly. “Let's be clear here—I'm not accusing them of cheating,” he said. “I give IBM full credit for getting it to that point, because if the AI wasn't working as well as it could have, then Watson wouldn't have buzzed in on certain categories or certain clues. So it's not like they were stealing any glory here. Watson absolutely did do what it said it did.

“It was good for IBM, it was good for Jeopardy!, it was good for me, it was good for Ken,” he said. “Everyone’s a winner.”

Not everyone is so sure —Jeopardy! devotees argue about this more fervently than ever, and even Jennings has doubts. “To this day, I still don't know—is that because Watson was hanging back, because they hadn't put it in its turbo mode?” he said of his and Rutter's victories during the practice games. “I don't know to what degree we just thought we were hanging with Watson, and it was intentionally buzzing slowly and responding incorrectly.”

Or it might have been something more prosaic: the dreaded situation that has robbed many a would-be Jeopardy! field of a win. “It could be that it just didn’t get a good spread of categories,” he said.

The buzzer speed argument has lost some of its mojo of late courtesy of, of all sources, Jeopardy! itself. For many years, the prevailing wisdom around the show was that buzzer speed was what set elite players apart. Most contestants know most of the answers most of the time, the typical refrain went—I wrote as much myself in years past—and therefore who got to ring in and rake in the dollars came down to who could buzz first.

Recently, however, that long-held truism has been shaken: The show has started releasing statistics about buzzer attempts , revealing that some contestants, especially those in the game's upper echelons, ring in much more often than others. It's not that the buzzer doesn't matter—it just matters much less than was previously believed, a shake-up that has reelevated the importance of subject-matter expertise.

As host, it now often falls to Jennings to study particularly striking data about buzzer use during games, noting players whose thumb-forwardness seems to point to especially broad trivia knowledge bases. “Now that we keep better stats at Jeopardy! , we know that the buzzer is not always the game changer,” he said.

Jennings is circumspect about the perpetual controversy around Watson. “All the things that bother people about Watson never bothered me, because those advantages are available to a human player as well,” he said. “I could sandbag in a practice match and then try something totally different during the game. That's not forbidden.

“Is it unfair that Watson could buzz faster than any human? No, that's just an advantage we know that computers have,” he said. He has seen the many complaints about Watson's speed, and the frequent suggestion that the computer's timing should have been slowed or perhaps swapped for a randomized selection of human response times.

“Maybe it would have been a better test of question answering, but it would not have been a better test of Jeopardy! play,” Jennings said. “That's just something a computer is good at in the Jeopardy! domain, the same way that a human is better at lateral thinking. I wasn't going to hamstring my lateral thinking to play more like a computer, so it didn't seem unfair to me that Watson had advantages.”

To this day, Jennings' Reddit username is “WatsonsBitch.”

Not long after ChatGPT's 2022 launch, Jennings wondered: How might the new generation of large language models do against Jeopardy! material?

During his reign as Jeopardy! host, Trebek typically arrived at the soundstage bright and early to review the upcoming tape day's clues in his office. Jennings, who has hosted the show since 2021, prefers to look clues over the night before, and thus found himself in a hotel room with a sheaf of fresh game material, prepped and vetted by Jeopardy! 's writers but never posted online or, indeed, seen by anyone except a handful of the show's staff.

Jennings pulled up ChatGPT and first tried entering clues from shows that had already aired. The LLM nailed them effortlessly. Then he put in some of the hot-off-the-presses clues that contestants would face the following day. Once again, ChatGPT was speedy and right every time. Jennings, who has long written his own trivia prompts outside Jeopardy! (including at Slate and, most recently, in a book published this summer), eventually tried submitting his own.

“If I made up a very esoteric, Jeopardy! -style wordplay, lateral-thinking bit of craziness—I could get crazy enough that it could get beat, but hardly ever,” Jennings said. “I had to write the world's most annoying Jeopardy! clues just to try to get it to be wrong. Maybe Watson was buzzing about half the time or slightly more. Today, humans would not have a chance. The equivalent algorithm would be buzzing practically 100 percent of the time.

“It's the ability to seemingly draw inference, where that was not a thing before,” added Jennings. He is confident that any kind of rematch would end in “another human loss.”

Nevertheless, a little more than a decade ago, both he and Rutter got their revenge on Watson—sort of.

In 2014, the pair found themselves at TCONA, a major trivia conference, where a favorite event called Knodgeball was scheduled to be played. In Knodgeball, teams of players face off while trivia questions are shouted from the sideline, racking up points both for answering prompts and for hurling dodgeballs at the opposing team.

Usually, the teams have equal members. But that year, an air purifier was christened “Watson” and anointed with a primitive copy of the computer's logo. Jennings and Rutter lined up on one side. Watson—“Watson”—was alone on the other; surely it didn't need any help from puny mortals.

The questions started coming as Jennings and Rutter called out answers, zinging balls over and over at Watson. Their onetime foe, or at least its unfortunate representation, remained steadfastly silent as it was pummeled again and again.

This time, humans won.