The first images revealing the mysterious implantation process of a human embryo have been published.

"We know more about the embryonic development of flies, fish, and chickens than about that of humans," says Samuel Ojosnegros, a researcher at the Institute for Bioengineering of Catalonia (IBEC). And he's right: during the first few weeks, the human embryo develops hidden inside the uterus, where the eyes of science can't see. What happens in that window of time between implantation and the first ultrasound remains a mystery.

However, that is beginning to change. A group of scientists from IBEC, including Ojosnegros, has managed to record the implantation of human embryos in real time for the first time. To achieve this, they used a novel laboratory system that simulates the outer layers of the uterus and allows them to recreate an implantation scenario as if it were happening inside a woman's body, only with donated eggs. The images were published this Friday in the journal Science Advances .

The achievement sheds light on those first days after implantation, which have been described as a true "black box" of human development. It is one of the most important moments in a person's life, when a tiny ball of cells transforms into the first draft of an individual who will be unique and unrepeatable.

“Only a third of fertilized embryos result in a live birth,” explains Ojosnegros, principal investigator of the Bioengineering for Reproductive Health group at IBEC. Thirty percent are lost before implantation and another 30% shortly afterward. “We don't know why it's so difficult, since implantation occurs inside the mother and can't be studied. The idea behind our work was to create a kind of artificial uterus so that the embryo can implant outside a human body and thus be able to research it,” he adds.

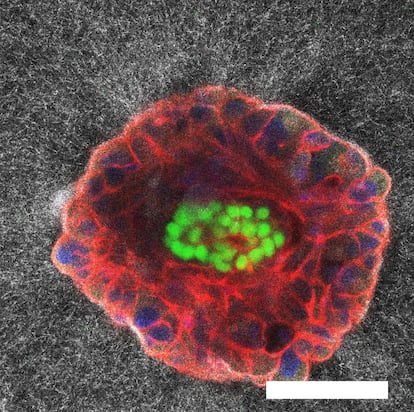

The newly published videos and photographs have revealed previously unknown details. "We have observed that human embryos bury themselves within the walls of the uterus, exerting considerable force during the process," notes Ojosnegros. The embryo, when it is five days old and microscopic in size, attaches itself to the surface of the uterus and digs a hole to enter it, reaching the blood vessels and beginning to feed. To do this, the embryo compacts itself and reveals the cells on its surface, specialized in adhering to and pulling on uterine tissue. All of this had already been studied extensively, but what was surprising about the images was the force that this tiny ball of cells was capable of exerting when it is still little more than a sack of genetic information.

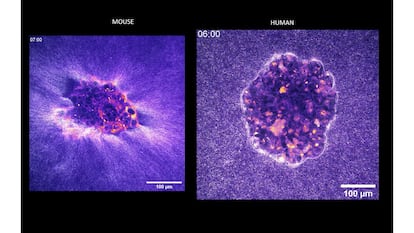

“We've compared human embryos with mouse embryos, and the human embryo is much more invasive, surprisingly invasive: it buries itself completely and exerts a lot of force to break through a fibrous, collagen-rich matrix,” Ojosnegros explains. Human embryos use proteins and molecular machinery to contract and generate that piercing force, while also releasing enzymes that degrade the surrounding tissue. The materials the tiny embryo must pass through are the same ones used to make tendons and cartilage, so the task isn't easy. This led researchers to suspect the reason why some women experience slight pain or bleeding at the beginning of pregnancy : because an embryo is slightly tearing the uterus to successfully implant itself there.

With mice, things are different: more gentle, so to speak. When the mouse embryo comes into contact with the uterus, it exerts force to adhere to its surface. But then, unlike in humans, the uterus adapts by folding around it, so that the embryo is encased in a kind of uterine crypt that greatly facilitates the rest of the process.

Technical and ethical barriersResearch in the field of human fertilization is very complex for many reasons, and one of them has to do with ethical limitations. In Spain, the law on assisted human reproduction techniques allows for in vitro embryo study up to 14 days after fertilization, after which the critical stage of development, the so-called "black box," begins. The embryos must then be destroyed.

Ojosnegros explains that, despite its limitations, Spanish regulations are quite "progressive" because they allow, for example, couples to donate embryos for research, which allows for experiments like the one this researcher and his team have just published.

This opens the door to increasing success rates in assisted reproduction , a type of treatment used by 40% of couples struggling to conceive naturally. The scientist sums up: "We are very excited that specialists in this field will adopt the system we have created to study implantation and will be able to answer their own questions about human fertility."

EL PAÍS