As a child, Stephanie-Joy was lonely, as a young person she was homeless and addicted, now she is a cheerful benefactor

A cheerful person. That's how Stephanie describes herself at her kitchen table at home. This is evident in the cheerful welcome she receives, accompanied by an enthusiastic young Labradoodle. The dog is busy with a squeaky toy, but Stephanie says it doesn't bother her. She has been severely hearing impaired since childhood and wears hearing aids.

She's doing well. She lives with her true love and has just brought joy to two hundred families living in poverty with a summer package full of things they wouldn't normally buy themselves: outdoor toys, good sunscreen, a holiday activity book. Now that the summer holidays are almost over, she's already busy preparing for Christmas. Every year, she makes hundreds of Christmas packages for low-income families, who normally don't receive them.

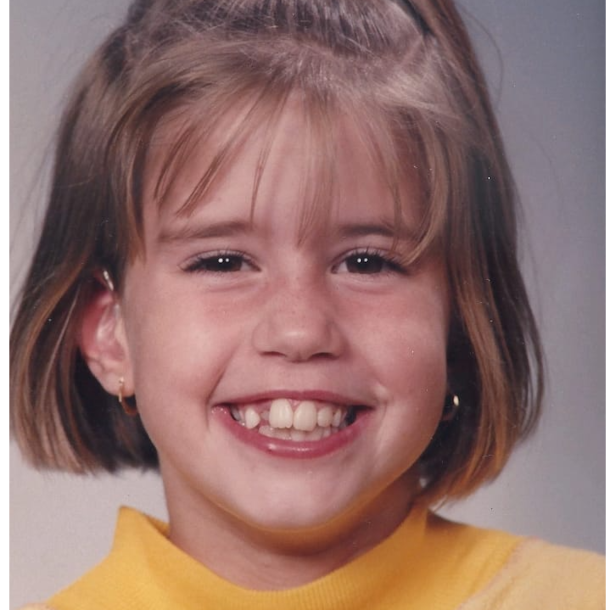

Hearing impairedAs a child, Stephanie had to attend a special education program because of her hearing, which was far from home. This made it difficult to make friends, as they didn't live close by. "I was a child who mainly played alone, with Playmobil, building castles, and that kind of thing." She also read a lot, "a real bookworm."

When she was six, her life changed completely. She was hit by a car in front of her parents' house. Her foot was completely shattered, resulting in permanent disability. She had to undergo numerous (reconstructive) surgeries and spent a lot of time in the hospital.

Consequences of a car accidentAs a child, she wasn't preoccupied with the impact such an accident would have on her life. Besides, her parents felt that crying wouldn't change the situation. The focus was on recovery and getting on with life. The accident wasn't discussed at home either. "There's a sense of loss there. How do you deal with the consequences? Maybe it was simply too unbearable for my parents to dwell on it for long."

Meanwhile, at school, she experienced both sides of her new disability. "Everyone wants to write on your cast and sends cards to the hospital; you're interesting," she says. "On the other hand, I couldn't keep up with the other children anymore. They ran, flew, jumped, roller-skated. As a young disabled person, I often got incredibly frustrated and simply pushed myself beyond the limits of pain. Participation was more important."

UnderdevelopedShe had a sheltered upbringing, she says, but that also meant she missed out on many normal experiences. Children weren't expected to know everything or be present at everything. "I didn't learn how public transportation worked until I was fourteen."

She also received little stimulation at school. During her time in special education, her parents were told they would likely never get a regular job because of her hearing loss. "I've come to realize that the years in special education were also years of social exclusion."

She also attended secondary school in a modified setting, with deaf and hearing-impaired children. During these years, Stephanie and her parents grew distant. This was due to puberty, but also to the many questions about the accident that her parents preferred not to answer, as that would reopen the wound. "We didn't understand each other."

Bomb burst"After school, I didn't leave the house. I wasn't social. Hearing loss makes you very insecure, and so do scars," she says. While youth care workers told her she simply needed social skills and to expand her network, she now knows she was dealing with underlying trauma from her accident.

When she later had to undergo reconstructive surgery, "the bombshell exploded." Talking about the accident at home was still impossible. "I finally ran away from home." That was the last straw for her parents. It wasn't going to happen anymore, not for Stephanie, but also not for her parents.

Placed out of homeAt fourteen, Stephanie was removed from her home. She ended up in a short-term crisis shelter for young people and from there moved to various supported living environments. She felt she didn't receive the emotional support she craved anywhere, due to inconsistent support and because she couldn't talk to her parents about "what really matters in life."

From the age of seventeen, she worked towards independent living in a group home, something she was expected to do from the moment she turned eighteen. It was a frightening thought. "I'm still a child," I thought. "And I've never been a carefree child."

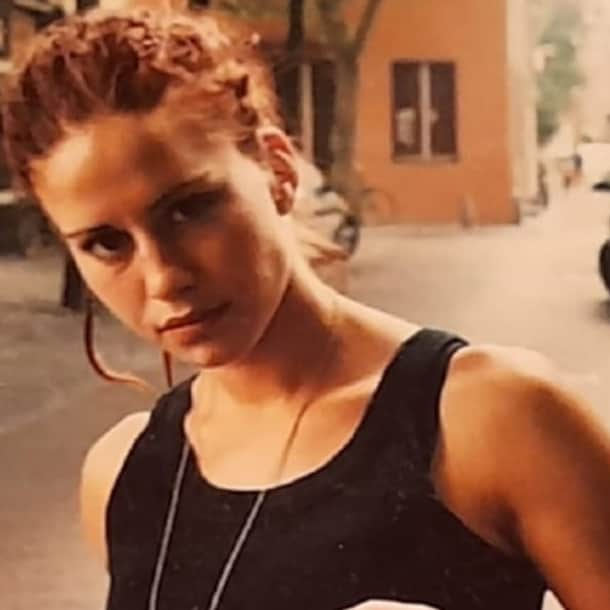

It made her rebellious. "One of my group members had an addicted father, and she kept going back to him," Stephanie says. "I was incredibly curious, so I tried cocaine there for the first time: smoking nothing but pipes of coke for three days."

In her memory, it was amazing. She was already smoking a lot of weed and continued to do so, but "that cocaine was a world of its own." "I found it incredibly exciting. I was also offered heroin, but I turned it down. Then I thought: if I do that, it's really not going to work out."

AddictionShe became addicted to cocaine. Initially, she paid for it with the student grant she received, as she had also started her studies around that time. But after a few months, she stole 50 euros from her mother. "That was the lowest point. That's when I really thought: I have to confess."

She was eventually kicked out of the group. Her parents were at their wits' end, unsure what to do for Stephanie. At a shelter for homeless youth in Haarlem, she entered survival mode. Her days revolved around getting weed, finding money, and figuring out where to put her things.

Encounter with faithShe ended up staying at a Salvation Army day and night shelter. "People from a Christian therapeutic rehabilitation center came by. They asked, 'Hey, do you want to join me for a hot meal?'"

She loved coming to that center, where she learned about God. When she was 19, she was baptized. "I always had pain in my foot, and after my baptism, it stopped. And that joint I lit afterward didn't get me high anymore. I don't know how, but I believe that with my baptism, everything from before is forgiven."

And that's where Stephanie's recovery began. Not immediately; she was still using speed, and things went wrong once more. During a church service, she "passed out" and had to be taken to the hospital. "After that, the pastor said, 'You have to make a choice.'"

RelapseAnd so she did: she moved into the church's rehab center and stayed sober for a year. But when the building had to be demolished, many residents returned to their old lives. Stephanie, too, relapsed. "I was assigned to care for someone who was withdrawing from heroin, and I had the key to the safe to provide methadone," she says. Methadone is a heroin substitute and is therefore used as a drug in withdrawal. "One day I said, 'Give me one of those pills.' That was the beginning of the end."

“The homeless shelter was afraid they would find me dead in bunk bed number five.”

She became addicted to methadone, developed an eating disorder, and eventually weighed only 84 pounds (38 kg). She continued attending church throughout this time, but her health deteriorated so drastically that she was no longer allowed to go to the homeless shelter. "They were afraid they'd find me dead in bunk number five."

Kicked the habitOnce again, she ended up in a new place, a supported living facility in Haarlem. "Everyone was mixed there. From people in forensic psychiatric care to serious heroin addicts. I lived there for quite a while."

But now things were different. Here were caregivers who "really made a difference." "They told me, 'You can go to school. Just go ahead and do it.'"

She kicked the habit, though it wasn't easy. Addiction treatment centers wouldn't help her because she had an eating disorder, and the eating disorder clinic wouldn't admit her because she was addicted. "Then I said, 'Well, I'm going to do it myself.'"

He succeeded: "I kicked the habit with my Bible under my arm."

A defining moment for Stephanie was when she went on a mission trip to Romania. She was 23 and helping Roma people. "All the kids just wanted to hold me and cuddle up to me," Stephanie says. "That's when I thought, 'What am I doing with my life?'"

Back in the Netherlands, she joined a writing club and wrote for the Street Newspaper, which she did well at. The instructor saw potential in her. "You could write a book," he said. "I have a publisher for you."

A little less than four months later, in 2009, the book "Daddy's Little Girl Sleeps on the Street" was published. It became a bestseller within a week. "That, of course, changed my life completely. Everyone wanted to talk to me, wanted to hear my story. That's when you're suddenly integrated into society."

Salvation ArmyShe was eventually assigned her own home from the Salvation Army shelter and started studying. First, she enrolled in the 21+ program at the Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences, as she hadn't finished high school, followed by a higher professional education program in social work.

One day I drove past a Salvation Army location and thought: I'll ask if they need any interns. They weren't actually interested in hiring first-year interns, but because she brought experience, they welcomed her. "Fantastic, of course!"

After her internship, she wanted to stay. She told her team leader she'd stay until she got a contract. That happened a year and a half after her internship began. Suddenly, she went from receiving Wajong benefits to around €1,200 a month. "I was as happy as a child."

Aid workerShe started working as a counselor at the Salvation Army, and after a few years, she began managing a residential group for people who are completely free of substance use. There, she and a team of people with lived experience helped people rebuild their lives after addiction.

She found support throughout this time in the church. First in the Pentecostal Church, where she felt brokenness was allowed and raw emotions were welcomed. But around 2017, she switched, "because I married a woman." "That's allowed in the Pentecostal Church, but you're not allowed to practice it. And I didn't feel like explaining to a pastor every time why I love my wife." She adds with a smile: "A lot, by the way. A fantastic woman. God truly gave her to me."

She transferred to the Salvation Army church, better known as the Corps. "You're always welcome there."

Christmas packagesIn 2010, when Stephanie got her own home, she also started the Christmas packages that would eventually lead to her foundation, Life With Joy. "When I was still a client, I saw employees receiving Christmas packages, and that made me a little jealous," she says. Later, as an employee of the Straatkrant, she received a Christmas package herself.

"People living in poverty are often told, 'Be happy you get something.' A Christmas gift shows that you belong, you are valuable."

The packages started small, with essentials. "I quickly realized they already know the bottom of the shelf," says Stephanie. So she moved on to more luxurious products. "Why does it always have to be a colorless store brand?"

She initially raised funds herself, then through social media appeals, and finally with donations. "All in all, 10,000 euros were donated," she says. It was Stephanie's wife who ultimately encouraged her to start a foundation.

Life With JoyThat happened in 2022. The foundation was officially registered, and hundreds of Christmas packages were assembled. A wonderful initiative, but often confronting, especially for the volunteers who deliver the packages. "They delivered a package to a family that didn't even have beds. Five of them were lying on the floor. The volunteers came back crying because of what they had seen."

“If I die now, at least know that I lived my life.”

Since its inception, it's gotten crazier and bigger every year. There's now a small warehouse and partnerships with organizations like the Poverty Fund and the Salvation Army. 450 Christmas hampers are distributed annually, along with around 200 summer hampers and children's hampers.

Stephanie also hopes to one day open her own shelter, where people with problems and addictions can receive support and encouragement. "We're going to fight for people to choose to live again, instead of just surviving."

SatisfyingWhen asked if she's proud of herself after all these years, there's a pause. "I get that question often, and I always say: I'm so grateful. I've truly been given grace, which is why I'm where I am today. I've had many opportunities and many people who have offered me a helping hand." Despite the difficult years, contact with her parents has always remained, and still is. "Always."

“I said to my wife the other day, if I die now, at least know that I have lived life.”

"I was placed out of my home, I was addicted, but I also kicked the habit. I wrote two books , I have my own foundation, got married and got two bachelor's degrees..." She concludes with a laugh: "So I've actually done well, right?"

Every Sunday, we publish a text-and-photo interview with someone who is doing or has experienced something special. This can be a life-changing event that they handle admirably. What all Sunday interviews have in common is that the story has a profound impact on the interviewee's life.

Are you or do you know someone who would be a good fit for a Sunday interview? Let us know via this email address: [email protected]

Read the previous Sunday interviews here .

RTL Nieuws

%3Aformat(jpeg)%3Afill(f8f8f8%2Ctrue)%2Fs3%2Fstatic.nrc.nl%2Ftaxonomy%2F25b53c9-Februari%252520Maxim%2525202025%25252004%2525201280.png&w=3840&q=100)

%2Fs3%2Fstatic.nrc.nl%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2025%2F09%2F03002720%2FPANAMA-US-VENEZUELA-NAVY-WARSHIP_69841638.jpg&w=3840&q=100)