What It Feels Like to Leave the Mormon Church

My family have been members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints since 1850, when my great-great-grandfather became our first Mormon convert and made the journey to Utah. Seven generations later, I was born in Colorado. My parents had planned to move to Utah after my father finished dental school, but my grandfather, already established there as a dentist himself, advised against it. “Too many dentists here,” he said. So they stayed in Colorado, an eight-hour drive from the place that held our family’s heart.

Every summer and Christmas meant pilgrimages to Utah. These weren’t just family visits—they were spiritual homecomings, reminders of where we came from and who we were meant to be. I loved those trips, playing with cousins who shared my faith, feeling connected to something larger than myself.

I am the youngest of four, and by the time I reached adulthood, the path seemed clear: serve a mission, serve the church, live my faith. Two of my older siblings had already served their missions, and I was excited to follow. The Mormon church operates on lay ministry—ordinary members “called” to leadership positions—and my parents had always answered those calls, serving in various roles. Church wasn’t merely what we did on Sundays; it was who we were.

There was one complication: I am gay.

The Mormon church’s position on homosexuality is slightly more nuanced than people may realize. Having same-gender attraction isn’t, in itself, considered sinful. A common term used by Mormons is worthiness, and while they never use the term unworthy, there are some acts that designate a constituent unworthy. One of those? Gay sex. Be as gay as you’d like, but remaining in the church means remaining celibate. Forever.

When I turned 18 and sat down with my bishop to discuss mission plans, I was honest about both being gay and about looking at pornography and masturbating, behaviors that required a period of repentance before serving a mission. I couldn’t go three months without one or the other, in part because I was grappling with feelings I didn’t understand and that had no healthy outlet.

The bishop and I decided I should wait until I had better control over my thoughts and actions. Instead of serving a mission, I enrolled in Brigham Young University–Hawaii, then transferred to BYU–Idaho. I spent several years trying to find a way to be both gay and Mormon. For a while, I found balance. I served in leadership positions—elder’s quorum, bishop’s secretary, choir director.

The church, to its credit, provided confidential spaces where I could discuss my struggles. When I had “slip-ups”—pornography or masturbation—I would confess, step back from my church duties for a few weeks of repentance, then return to full participation. (This chastisement was meted out for any individual dabbling in sexual activity or masturbation, regardless of sexual orientation.) This cycle became familiar, even comfortable in its own way.

By 21, I discovered online communities of gay Mormons navigating the same challenges. Finally, I felt understood. Through one of these online groups, I met someone who lived in another state. We planned a visit—just for lunch, just a conversation with two people who understand each other. We ended up kissing in my car. Suddenly, everything I thought I knew about my future shifted. Maybe I didn’t have to be alone forever.

This led to intense internal conflict. At 24, I began a virtual relationship with another gay Mormon man. We never met in person, but we were emotionally intimate and sexted often. I was unprepared for the complexity of wanting things that seemed mutually exclusive: to be faithful to my religion and to experience love.

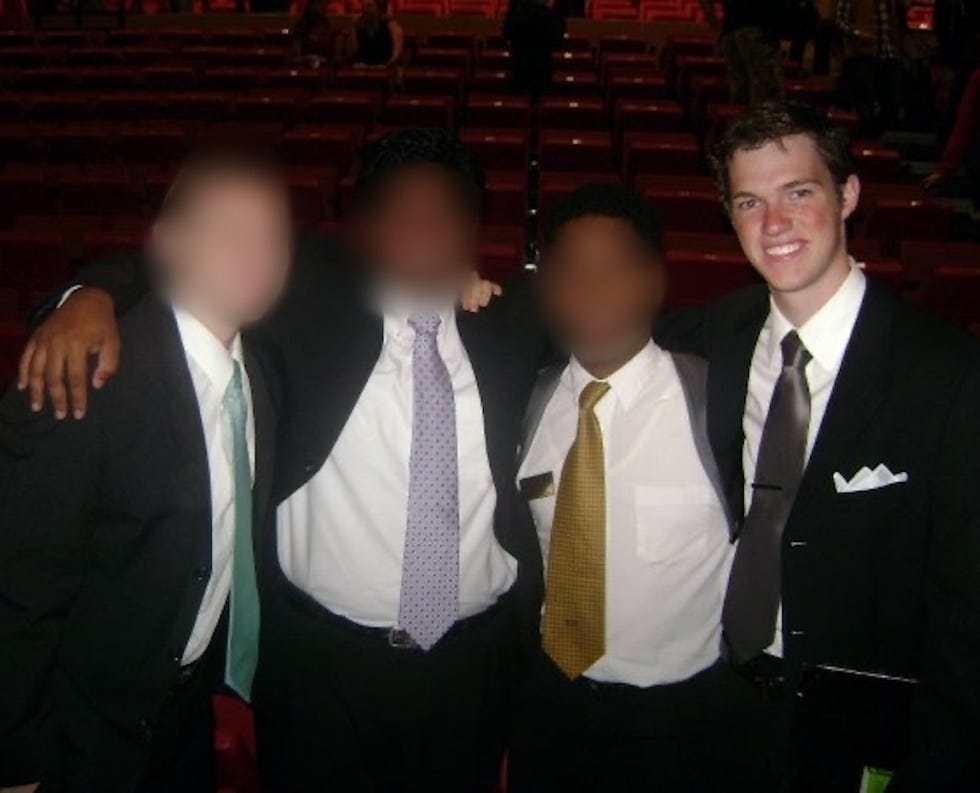

Brett Evans at BYU.

My emotional immaturity resulted in my engaging with this man, then pulling back dramatically when the guilt became overwhelming. After months of this, he confronted me. When I told him I needed to step back, to figure things out, he was upset. With the dissolution of our romance, he felt a crucial support system had also disappeared. I didn't hear from him for months.

Fast-forward to May 2014, my final semester at BYU–Idaho. Whether you’re Mormon or not, BYU students sign a school code of conduct. Part of it covers academic standards (no cheating, for example) and the rest addresses ethical standards (no drinking, smoking, drugs, or premarital sex). Transgressions are adjudicated by the Honor Code office, and it was this very office I found myself being summoned to on a bright spring day.

A middle-aged administrator asked friendly queries about my background and studies before revealing why I was there: Someone had reported my online communications and relationships with other gay Mormon men. The invasive questioning that followed was frightening. He wanted details about our network, information about meetings, and for me to identify other members. “I know you’ve been exchanging sexual videos with someone,” he gravely levied.

The outcome was devastating: a four-semester suspension that would effectively prevent me from graduating for three years. I was nine credits short of my degree. I was hurt and confused, so I reached out to the man with whom I had been involved, leaving a voicemail asking if this was his doing.

He emailed a week later: “I wanted to make you feel as miserable as you made me feel.”

What surprised me most was my parents’s reaction. They were furious—not at me but at the school. My mother called the Honor Code office to advocate for me, and the administrator read her intimate excerpts from my private conversations. For a Mormon mother to hear those details about her son’s life was devastating, but it also opened her eyes to how the institution was treating her child.

The irony was that, ecclesiastically, I had already been through the repentance process for my actions. My local bishop had worked with me, and I had been forgiven in the eyes of the church. But BYU operated under different rules. I appealed the decision, appearing before a board with my bishop beside me, arguing that I had already been religiously absolved and that the investigation felt more like a witch hunt than a disciplinary process. My appeal was denied.

I took my lumps and moved to California, where I found work in journalism, the field I had been studying for. In that sense, things worked out. But I also carried the weight of six years of education with no degree to show for it and the deeper question of whether I could continue trying to be both gay and Mormon. I decided to give the church another honest try.

I found a local congregation, began tithing again, and attended services earnestly every Sunday. I wrestled with the notion that I am the child of a loving God and the image in which He created me includes homosexuality. Could I make peace with a lifetime of celibacy and find fulfillment in service to God and others?

The answer came during an evening prayer session. I was contemplating eliminating all gay influences from my life—the support groups, friendships, and online communities that had helped me. I was prepared to find a therapist and commit fully to the LDS way, if that’s what God wanted from me. But as I prayed about this path, I felt only anxiety and fear.

Brett and his partner.

Then a different thought entered my mind: What if the church is wrong about this?

The overwhelming peace that followed that question was my sign, spiritual confirmation I had been seeking. It wasn’t the answer I expected, but it was the answer I needed. When I called my parents the following morning to tell them I was leaving the church, I explained what had happened during my prayer. I told them I had given everything I could to try to make it work, but I finally felt peace about walking away. My mother’s response stays with me: “You will always have a seat at our table. You’re always welcome in our home. And so is whomever you love.”

That was in 2016. I continued to sporadically attend church to support my parents, if we were together. Until 2021. That’s when Elder Jeffrey R. Holland gave a speech at BYU warning against becoming too accepting of gay marriage. Holland suggested Mormons needed to do as the pioneers did, building the church with a shovel in one hand and a musket in the other—disturbing comments to a captive audience that may take it too literally. This was the final straw for some of my siblings, and they also left the church. Even my parents expressed concern and acknowledged that the church wasn’t the best place for me.

We still attend a Christmas service together each year, my one concession to the faith that shaped our family for seven generations. We’re prepared to walk out if anyone says anything harmful about marginalized communities, but Christmas sermons tend to focus on Jesus and love, so we stay.

I haven’t removed my name from church records, though. That process requires paperwork, meetings with local leaders, and notarized documents. This institution doesn’t deserve any more of my effort or energy.

I am fortunate to have a support system that many people leaving the church don’t have. My family’s love never wavered; my friends were accepting and kind. This made all the difference in how I processed leaving a faith that had defined my identity for two decades.

I feel empathy for my parents, who raised four children in a faith they believed would bind our family together forever, only to watch all of us walk away from it. That cannot be easy. But I also know they did their best with what they believed was true, and they continue to love us unconditionally.

I never finished my undergraduate degree, though I hope to someday. My career in journalism has progressed well without it, but completing that degree would be a point of pride—closure on a chapter of my life that ended so abruptly.

Today, I am very happy, engaged to a loving man with whom I can’t wait to spend the rest of my life. What I’ve learned is that sometimes the most faithful thing you can do is admit that a path isn’t working for you, even when it works for people you love and respect. The church wanted me to be a good Mormon who happened to be gay. I needed to be a whole person who happened to have been Mormon.

esquire