Big Shoulders Are In

Several months ago, after internet trolls dragged the actress Sydney Sweeney and her bulked-up new physique for the upcoming biopic of legendary boxer Christy Martin—bemoaning that they found her “chunky” and less attractive—Sweeney clapped back with a video compilation of the insults (and their authors) and a training montage of herself rolling truck tires, weight lifting, and sparring in the ring. No caption—she let her biceps do the talking.

Sweeney, who has dealt with body-shaming for much of her career—the irony being that until recently it has been based on the hypersexualized assumption that, as she put it, “I have big boobs, I’m blonde, and that’s all I have”—is the latest star to join the Hollywood gun show, a lineup that includes Ryan Destiny transforming herself to play two-time Olympic champion boxer Claressa Shields in The Fire Inside, and Kristen Stewart and Katy O’Brian in last year’s steroid-pumped bodybuilding noir Love Lies Bleeding.

It’s all part of a pop-culture-fueled fitness trend toward muscle that prioritizes the female gaze—and well-being—over the male. Big shoulders are in. When it comes to strength training, the word is out: Women need to lift, and lift heavy, to build up muscle mass. That’s what helps stave off the loss of bone and muscle as we age.

Katy O’Brian and Kristen Stewart in Love Lies Bleeding.

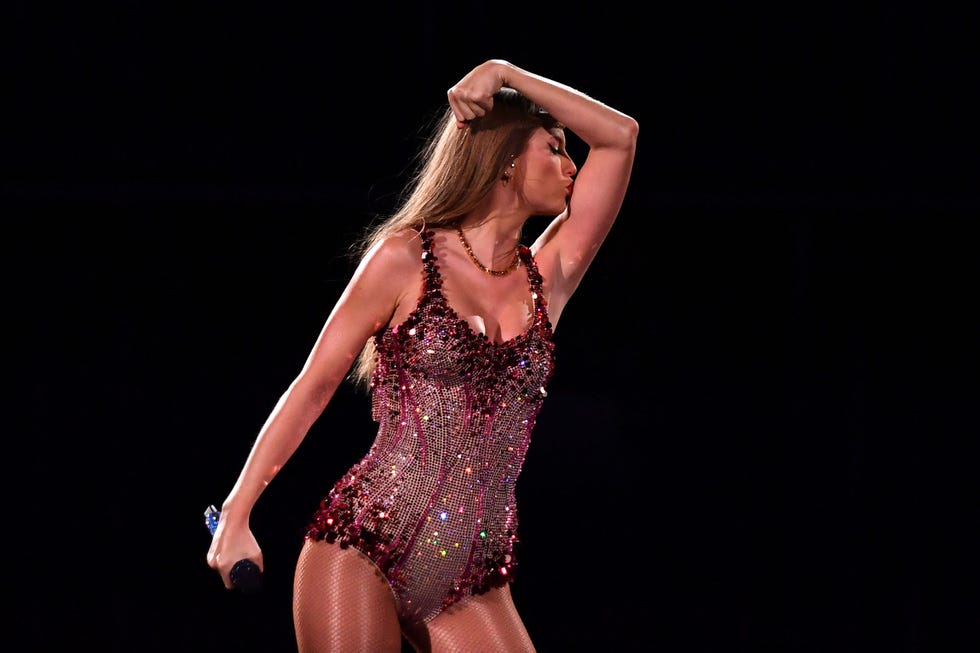

The movement is only, well, growing. On TikTok, self-proclaimed “muscle mommies” and “muscle mamis” share tips about maximizing protein intake, macros, and gains. (No more dainty “toning and lengthening” via Pilates.) Even Taylor Swift, over the arc of her five-continent Eras Tour, made a point of flexing and kissing her own biceps ahead of performing “The Man,” a song that skewers double standards for how men and women are treated in society. Fans lost their minds, but this power pose was far from frivolous.

Swift’s muscles meant something: Here was a record-breaking billion-dollar superstar, rocking the world on a seismic scale, and physically performing that flex over a nearly three-and-a-half-hour set for all to see. As a younger artist, she’d talked about her own struggles with disordered eating and body image; here, she was visibly bigger and stronger. She was endurance-entertainment-athlete-as-role-model, night after night, for the millions of girls in the audience.

Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour, was endurance-entertainment-athlete-as-role-model, night after night, for the millions of girls in the audience.

Is it any wonder that we are actively confronting the regressive masculinist currents of our time with daily doses of iron and rage workouts? Even influential public intellectuals like Tressie McMillan Cottom are telling us how they’re lifting and gritting their way through the political chaos: “I focus on how hard this is so I can forget how hard everything else is for a few hours a week,” Cottom wrote. Remember that muscle is action.

“Is it any wonder that we are actively confronting the regressive masculinist currents of our time with daily doses of iron and rage workouts?”

I’ve spent the last few years writing a book about muscle and what it means, and this is what I know: Muscles are about potential, and strength, and owning your own strength. For women, the work of building our own muscles teaches us not to let others take away that hard-won power without a fight.

Our society’s relationship with strong female bodies has long been deeply conflicted. In America, the history of strong women goes back more than two centuries, a constantly shifting period in which circus performers, trapeze artists, bodybuilders, gymnasts, and other athletes have been greeted variously as (a) daring and fascinating, (b) exotic and titillating, or (c) disturbing and morally repugnant.

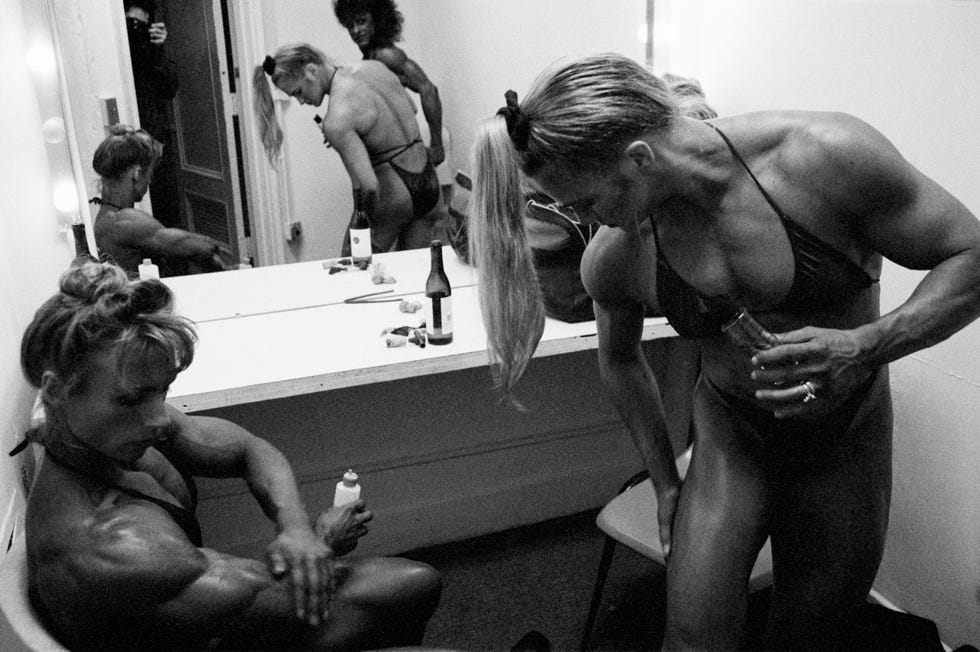

Participants in the Women’s Kings County Open Body division championship in Brooklyn, New York in 1982.

If it seems outrageous that men are threatened by female strength, remember that it’s a self-perpetuating tale as old as time. Binary thinking about gender roles has long encouraged a worldview in which muscularity and physical strength for women is a threat to societal order, domestic harmony, and reproductive responsibility. Strength, of course, is not zero-sum. If I am strong, you can be strong, too. But witness the gender rhetoric in Washington designed to force us all back into this binary, and you will feel a familiar whiplash.

During the 19th-century women’s suffrage movement, activists like Charlotte Perkins Gilman believed in physical fitness as a strategy for emancipation. “The idea was that we must have physical health to be free women,” says Jan Todd, the sports historian and powerlifting pioneer. Exercise was a way for women to get control of their bodies and reproductive lives—to gain political power, one needed physical power.

“For women, the work of building our own muscles teaches us not to let others take away that hard-won power without a fight.”

Female bodybuilders compete in the 1993 Ms. Olympia bodybuilding competition held at the Beacon Theatre in New York City.

As rugby star Ilona Maher puts it, “Women can be strong, and they can have broad shoulders, and they can take up space.” Maher has almost single-handedly changed the conversation around women in sports, body image, and beauty with her hilarious, charismatic viral videos on social media, many done with the comedic timing of Lucille Ball (her IG post “Dear girl with the big shoulders” is especially resonant).

After winning the bronze medal in women’s rugby sevens with Team USA at the Paris Olympics, she modeled for Sports Illustrated Swimsuit, elegantly quick-stepped her way to second place on Dancing With the Stars, and made her Premiership Women’s Rugby debut with the Bristol Bears, breaking attendance records in the process.

Part of Maher’s effectiveness as an ambassador of muscle is her openness and vulnerability, which sits right alongside her confidence and pride about what that muscular body allows her to do in the world. To all the young girls out there, she says: “This is my body, and my body is meant to be big and powerful and strong.” And to all the haters: “I’m going to the Olympics, and you’re not.” She knows that muscle is power.

Rugby and social media star Ilona Maher.

Last fall, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art mounted an exhibition called Get in the Game: Sports, Art, Culture. It was the largest presentation in the museum’s history, and hugely popular; this year, it will travel to Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, and the Pérez Art Museum Miami. One weekend, I led a series of “muscle walks” through the show, introducing museum-goers to various artworks through the lens of muscle, including a glorious series of images of the Brown University women’s rugby team, shot by the photographer Alejandra Carles-Tolra.

In “Bruises, Legs, and Sweat,” the four large-format photographs spotlight individual faces, legs, and torsos in the scrum, the muscular whole moving as a single powerful being. Carles-Tolra’s work challenges audiences on their own assumptions about what’s masculine and what’s feminine, and to think about what it is to be a female athlete in a male-dominated sport—and, by extension, a female in a male-dominated world.

Perhaps it helps to know that muscle itself is one of the most adaptable tissues in the human body. Minute to minute, it’s reacting to changes in the environment and responding with what is needed, from the moment you wake up to when you go to sleep. And so are we. Note that in the male-dominated sport of rugby, Maher is now the most-followed rugby player in the world on social media.

In a post-election political and cultural landscape where gender equity is under attack and tech-bro titans are doubling down on the manosphere, the resistance will need to be visible—written, worn, even physically carried on the body itself. So bring that “girl with the big shoulders” energy. Flex in all the ways that matter. Remember what muscles allow you to do, within the body and beyond.

This story appears in the May 2025 issue of ELLE.

elle