What I Didn’t Understand About My Autistic Son, and What I’m Learning Now That He’s an Adult

When my son Sam was seven or eight years old, he spent a good bit of time on weekends upside down on a floral-print armchair in our living room. In one hand, he held Batman; in the other, Robin. Surely the Joker lurked nearby. I would be sitting on the couch a few feet away, legal pad in my lap, writing. I’m a magazine journalist.

Sam and I could stay locked in our spots for hours at a time. I was sure he was happy as could be, in the land of escape, good guys winning over bad.

But it’s etched in memory for Sam, what it was really like for him in that living room when he was young:

Your pen on that page was like you’re trying to rip through the paper, like you’re mad. You had told me what you were doing—writing. But I thought it might be a bad thing, like it would make you mad. But then you stop. There was nothing in your face. It looked like you were looking at me. Your eyes didn’t move. You’d start scratching again on that pad. I watched. It was worse when you stopped. You were right there, you didn’t look happy, there was nothing I could see in your eyes. So I’d turn in my chair away from you. That’s all I could do.

What I saw then was a boy thrusting away, Batman taking control, Robin providing support, in need of nothing from me—or so I thought. Which gave me license to stay right there, locked in my own mind.

Sam had no interest in eating or looking out at the day or even taking a pee. Come to think of it, I didn’t bother with those things either—I was working.

He seemed fine. Though it was quite the opposite of that.

Sam is autistic. There is still no grounding, medically speaking, on what autism is, no neurological answer that nails it. It is defined by a spectrum of symptoms—thus the common refrain “he’s on the spectrum”—and what that means, for any one person, is particular. As Sam says, “If you’ve met someone with autism, you’ve met one person with autism.” Diagnosed at fifteen with Asperger’s, which tends to manifest in social awkwardness and a narrow range of all-absorbing interests, Sam is “high functioning” (the DSM, the widely used American Psychiatric Association guidebook for mental disorders, no longer uses Asperger’s as a classification): He is now thirty-six, married with two young sons, a college graduate, gainfully employed as a lab tech at a pharmaceutical company, and his take on the world is adamant and unique, with certain challenges. For example, he doesn’t drive, having flunked the test a half-dozen times over the strange angles demanded of parallel parking. Organizing his life, even along the lines of, say, cleaning a bathroom, is largely a mystery to him, still uncracked.

Moreover, his perception of things around him, and what any given moment might require him to do, can seem off. Let’s say we walk up to the front door of his house together; I’m carrying a heavy box of books to give him as he is talking to me about the Grateful Dead knockoff band he saw the night before. Sam loves the Grateful Dead. At the door, we both stop. He is waiting. So am I—for him to open the door. Sam doesn’t see doing that as the necessary or natural gesture; that’s the challenge autism gives him, his mind dancing in several directions at once but not readily landing on this moment. A thousand times, I have said some version of this to him: “Sam, open the door.”

He had a tough time, growing up. Sam went to several schools as his mother, Karen, and I tried to find the right environment for him. She made it her mission to give him the best chance to succeed. He had few friends, was frequently bullied, and had little sense for most of his childhood of how to fit in. “I spent a lot of time by myself when I was young,” Sam says now, “and the feeling was everything was happening somewhere else, some place I wasn’t invited. And I didn’t know why.” Meanwhile, his brother, Nick, four years younger, flourished, both in school and with other kids.

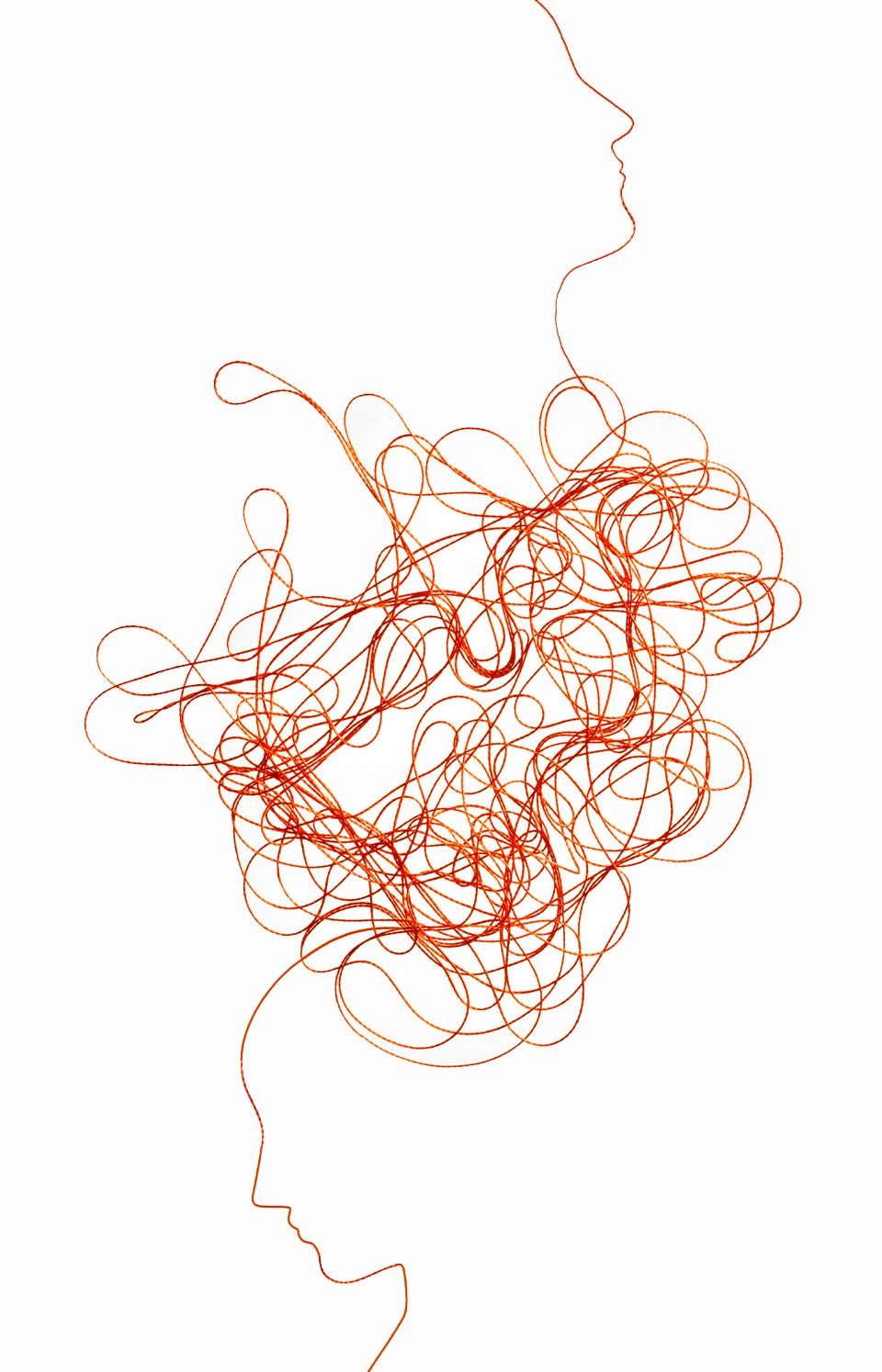

The author and his son Sam, who has autism. “I spent a lot of time by myself when I was young,” Sam says now, “and the feeling was everything was happening somewhere else, some place I wasn’t invited. And I didn’t know why.”

It is still hard for me to hear Sam talk about how alone he felt as a child, but he has changed a great deal, beginning with making a decision, in his mid-twenties, that he was going to start over. That he was going to look at himself as just fine the way he is and that the way he perceives things and functions—from the way he holds a pencil to how he might need a boss at work to deliver instructions one step at a time—must simply be accepted.

Such a self-declaration is one thing; learning to fit in ways that others find palatable, in ways that allow him to flourish, another.

I had always viewed him, even in his victories as he grew up, in terms of his autism. A psychologist once told Karen and me that Sam was generally behind developmentally but would get there—eventually. My advice to him had been: You can objectify your disability. It is a challenge but not good or bad; it’s merely a fact. As if his job was to dismiss his differences and chase what was normal, whatever that might mean.

Now Sam was done with that. He turned my advice on its head.

His mission became almost a matter of rights, to prove a point, to flatten a question: Why do you neurotypical people think you have all the answers? He simply has a different purchase on what’s what, and he decided it was high time that everyone else, including his parents—especially his parents—understand that the autistic mind can be legitimate on its own terms. As Sam puts it, “You’re not respecting people on the spectrum by treating us like a project.” Trapped in a box of disability, he started punching his way out.

One of Sam's starting places was bringing his mother, and then me, into therapy with him, where he went all the way back to that young boy playing in the living room while I sat there and worked. Sam said one of the most painful things anyone ever has ever said to me, in therapy: “I didn’t think you wanted to be with me.” I was so stunned by that I said nothing.

He meant what he said literally, that I would rather have been off working in my third-floor office or at the Philadelphia magazine where I was an editor. But he meant it in another way as well: that even when we were together, I didn’t see him for who he really was. That I wasn’t with him, in the way he perceives things, in how Sam thinks.

I have gained some perspective, over the years, on how his mind works. This insight from Spectrum, an online autism journal, hit me as profound: “For a person with autism, the world never stops being surprising”—that is, new, and often overwhelming. Thinking back to our living room when he was young, where he played Batman and I worked, I realized that everything he took in—and the connection he wanted—overwhelmed his understanding. Never mind that he had seen me writing on my legal pads before, a lot. My pen on that page as if I were ripping through it, as if I were angry, and staring into space as I worked, was new and strange every time he saw it, a sensory overload for Sam. And he had no idea how to break through that to me.

Sam said one of the most painful things anyone has ever said to me, in therapy: I didn’t think you wanted to be with me.

Which was a window into the depth of his challenge, and how brave he was, as a young adult, in demanding that however his mind works, it is legitimate, simply because it is his. No matter where that might take him.

Even as Sam had emerged, post-college, to live on his own in an apartment near Karen and me, to hold down a job as a teaching assistant at the private school for kids with learning challenges where Karen is an administrator, it was a life that did not fit, that he had no clue how to manage. “I was getting high every night and living in my own filth,” he says now. He couldn’t sleep in the double bed that had come from his childhood bedroom, since having no one to share it with made his loneliness worse. Instead, the spine of a broken futon drilled up into his back in his tiny living room, night after night, the litter of those hours getting wasted piling up on the floor before him.

One night, he went out to his apartment building’s courtyard and railed at no one in particular, up at the sky, the heavens, as if he were challenging God on why he had no one at all to love: “Why am I all alone? Why me? WHY?”

And then a woman appeared.

Sam met Gisette, who is smart and funny and warm, on an online dating site when he was twenty-five, and immediately they fell in love. Karen and I liked her right off. Sam was open about his autism (not that he could slide it out of sight), and she dismissed it. Gisette grew up in Queens, a city girl who’d been around the block, and somebody a little different didn’t faze her. It was, in fact, quite the opposite: His willingness to be himself, no matter how rough around the edges, took her by storm, just as her sureness touched him.

Off he went with her, and away from his mother and me, to her house in the suburbs of Philly. Sam was almost, for a time, totally removed—except to bring us into therapy with him and vent. He had decided, come hell or high water, he was going to engage the world, and figure out what he would do, on his own terms. Which included how to be a man and a husband, neither of which he felt he’d learned from me.

However, he had no idea how to get there, starting with how to get out of the new bare-bones job he’d taken teaching very young autistic children basic skills. Gisette complained to him that he didn’t seem to have opinions of his own, that she never knew what he was thinking. Meanwhile, he promised Gisette that he’d support her, that he would take care of them both as they had a family. But how? Sam had the desire to launch a career but no path—at least not one that he could readily go down. He spoke at St. Joseph’s University and other local schools in small forums about life on the spectrum and proposed a program to St. Joe’s on how to ease the social anxiety of students there with autism. They showed interest—to Sam that meant he was in. His moneymaker! In the end, they passed on the idea.

It was all so . . . naked and ad hoc. As if he had no choice but to strip away what he’d been told about how to function—there’d been a lot of emphasis on general comportment, such as making eye contact with someone talking to him and paying attention to what they were saying, plus maybe taking a moment in the morning to actually slip his belt through all the loops on his pants. Was that stuff really so important? It was time to figure out, in his own way, what was. The practical challenge of autism had hit home—whoever he was, whatever he might be able to do, often didn’t fit the workaday world. And that tested his young marriage. (Much of this I learned long after the fact.)

When our grandson Sky was born eight years ago, Karen and I were invited back into Sam’s life. One night, after a bad fight with Gisette in the period when his promise of supporting her wasn’t happening, he called us beside himself—as if he’d lost all sense of who he was and what he wanted. Outside his rowhouse, I held either side of Sam’s head with the palms of my hands and stared into his eyes, giving him no chance to avoid mine. I asked him what, exactly, he was going to do.

He had no idea. What did he want to do? He had no idea—not at that moment.

Yet he remained determined, to figure things out himself.

Slowly, his shoot-from-the-hip promises to Gisette stopped. Sam got a job as a lab tech at the pharmaceutical-testing company where she worked; getting away from chaotic work trying to help hyper-needy kids (even if, one-on-one, he often had a strong feel for their dilemmas) to the more direct realm of science helped. “As soon as I stepped into the lab there,” Sam says now, “it made sense to me.” His life with Gisette got calmer.

It is a given for people on the spectrum that they often think in a linear way, that they get on a track, ride it deep, and have trouble seeing anything left or right of that journey. Which might seem at odds with Sam being overwhelmed with too much sensory input, but getting on a singular track is a response to that risk, a way to cope. I was now seeing it in Sam, in the unyielding depth of his love for Gisette expressly because it is the path he had found, and needed.

Finally, I began to see that my son–my autistic son was offering me something large. That he was shifting our relationship from blame to understanding of me.

And I watched Sam as a father intently.

One long spring weekend when Sky was two, we rented a house on a lake in the Poconos in upstate Pennsylvania. My younger son, Nick, and his partner, Shawn—then a couple, now married—came, and so did Gisette, Sam, and Sky. I marveled at what I witnessed there: how Sam was utterly dialed in to Sky, teasing him to go swimming, though it was far too cold to swim. This didn’t deter Sam, who lured Sky to the end of the dock and, standing waist deep in the lake, held his son aloft as he walked his way to deeper water, Sky laughing as Sam started to lower him slowly into . . . Sky shrieked as his butt touched down. Then Sam would walk him back to the dock, but Sky wanted more, so they’d tiptoe out into the water—or at least Sam would, holding Sky—all over again, lowering him into . . . Daddy! It’s cold! It went on like that for probably an hour and a half, as if Sam were immune to how freezing he had to be.

What touched me, what seemed kind of remarkable in something otherwise ordinary, was how Sam didn’t have a moment of saying, or intimating, or as far as I could tell feeling, Okay, enough, Sky, time for me to come out. To dry off, get dressed, get warm by the fire the rest of us huddled around. It wasn’t that Sam didn’t have other things to do, and I’m sure he was freezing. But he had found the best thing to do, and he would do that, and only that, for as long as he possibly could, a feeling he remembers well: “There was no decision to make. It was simply too good to stop.”

Sam, his son Sky, and the author at a baseball game in 2024. “We’re told that we’re broken,” Sam says now. “But God made us this way. We’re not broken. Why is the world saying, You can’t do this? I’m here to say Fuck you. We’re going to keep changing the world, and that’s what I’m passionate about.”

There it was, the directness of his thinking paying dividends: If he often took in too much of what surrounded him and couldn’t quickly decipher what was important and what should be ignored, once he dialed in, Sam really dialed in.

This was where he landed—with himself, trusting himself, which was a sea change. Along the way, he became a man of faith, a believer in God. When they were boys, Karen and I had taken our sons to a Quaker meeting for several years, though all of us had lapsed from that. Sam’s faith has helped him find focus and calm, but discovering who he is goes back to that decision he made: He would go at things in his own way, by his own lights, with the mind he was given.

Not that it has been easy, not that the challenges of autism went away, but the grounding he demanded was so simple, and so direct, the platform that he had to have, a zeroed-in trust that there was no denying: I am just fine exactly the way I am.

As Sam's sons—eight-year-old Sky’s brother Isaac is three—have been a conduit back to him, and to Gisette as well, which I’ve certainly welcomed, a door opened for him to start a new quest.

Sam began wondering, with his trademark bluntness, “Why did you work so much, Dad? Why were you so buried in your own thing?” And: “What was it like, having an autistic son?” One night at their house, when I was picking up Sky for a couple days at mine, Gisette asked me, “Did you want to leave when Sam was young?”

Never, I told her, not at all. Which was true. But those were, to say the least, hard questions, and I could feel both Sam and Gisette in them, how they wondered about me. Sam told me in therapy that he knew I had always loved him, but why didn’t I take the time and energy to see him as he needed to be seen?

Part of me was thinking, Enough, Sam. As you’ve come a long way to yourself, so have we. But he still wanted me to open up, to be vulnerable with him. (Oh, if you only knew, Sam, how difficult it was for me to learn, mostly long after the fact, how you were bullied as a young boy, for example. That’s exactly his point—he doesn’t know how I felt about that, and much more.)

His questions, especially the one that’s really a demand—“Why did you work so much, Dad?”—led to something new. Sam had now landed, with me, on the most basic challenge there is: Who are you, Dad?

As a boy, he had taken what his mother and I told him as a sort of gospel, as children will often do to a point—his point lasted into college and beyond, including that he should take his time with Gisette at first, not leap right in. Be measured, Sam. Slow down. Which, he says, almost ruined things initially between them when he was utterly sure about her from the get-go. Following our advice was over now. If it had taken Sam longer to come to himself than other kids, when he did, when he got there, he and I were in a whole new territory.

Who are you, Dad? It was kind of a big ask.

Was I willing to take on not just how I raised Sam but to look hard at my own path, some things in my story that I take as givens? My disconnect from my own father. My obsession with work. My way of spending long swaths of time deep in my own mind, even as people who love me would like to be let in a lot more. He was asking me to deal with parts of myself that I elbowed aside a long time ago on my way to finding the thing I love to do. Writing.

Forty years ago, I left the college town I’d been hanging around in far too long in Pennsylvania, moved to the Bay Area, got a job making pizza, rented a small apartment in North Oakland (you could rent an apartment with a pizza job back then), and proceeded to cut a hole the size of a volleyball high in the door of a walk-in closet. I screwed a fan into this hole and punched another hole, low, in a wall so that I could sit at the table I’d built in there, with a stack of legal pads at the ready, light a Salem, hold it near my ear, and let the fan pull it up in a firm line, out into the living room where Karen, who’d followed me west from Pennsylvania, would be lying on the couch, reading. That walk-in closet was my stake in the ground. I was a writer.

And in a way, diving into that, into work, Sam made easy a decade later, in how he seemed submerged in his own world—back to Batman and Robin upside down on that flowered armchair and any number of ways he seemed happily lost in fantasy.

What a long ride we’ve taken, Sam and I. Finally, I began to see that my son—my autistic son—was offering me something large. That he was shifting our relationship from blame to understanding—of me. It felt like a challenge. Did I have the guts to open up?

As a young boy, on weekends and weekday evenings, my father would be in his workshop, where I was supposed to be too, learning how to build things. But my father’s near silence, giving me no access to his inner weather, kept me away. I stayed in the house watching sports or simply fantasizing about them, staring at my hands as I lay on a couch, at fingers that writhed as if furious to tie some knot. The knot of my imagination. A game played in my head for hours at a time.

I was aware, even then, as a child, that I was a little . . . different.

In the autism community, my physical acting out of my daydreams would be called stimming, a place I went to as if I had no choice. (My family gave it the euphemism “thinking.”) Whether this makes me a fellow traveler with Sam, with a possible diagnosis on the autism spectrum myself, seems both highly plausible and beside the point. But this isn’t: Sam is saying that that boy on the couch is alive and well and would like to have a word with me. Long ago, I made a decision. I shut that boy down and I moved on from him. That’s a dangerous thing to do.

I am afraid of one possibility when I allow myself to think back: that I did not exist. That my world was so thin, so empty, so all in my head, that I was . . . nothing. And now, stripped down in light of this walk I’ve been taking with Sam, honoring his questions about me as if I had no choice since he’s had to ask equally fundamental questions of himself, there’s the truth that I can’t escape: I still have that fear. That I need my work because I don’t exist without it.

Sam wants me to pull a chair up next to that boy on the couch dreaming his days away and to forgive him for his oddness. To feel what that boy felt, a stranger in a strange land, and to accept him. It’s the way to be released, into a much gentler view of what I felt I had to become.

Which mirrors what Sam had to do. To champion the boy he was, who had such a rough time, in order to believe in the man he could become.

“Most people like me who are thirty years old are living in their mother’s basement,” Sam has told me (and part of the reason it is the mother’s basement is because the father has fled over the emotional toll of raising an autistic son). He shares that not so much to brag about how well he’s done as to bemoan how badly we generally understand children like him. If he hadn’t found his way, Sam could have been there too—in his mother’s basement with an absent father—never sorting out a way to live with Gisette, and how to work, and how to raise his sons.

And now my son is not giving us a choice: “We’re told that we’re broken. But God made us this way. We’re not broken. Why is the world saying You can’t do this? I’m here to say Fuck you. We’re going to keep changing the world, and that’s what I’m passionate about.”

That makes me smile. How did he get there, so fiery? (Well, at this point I know the answer, that Sam felt he had been held back so long that once he emerged, he burst forward—but still, it’s stunning.) You go, Sam!

Now the conversation I’m having with him has a new dimension. Though we are still, of course, father and son, we are also two men out and about living our lives, and as he tests me—and teases me—about the novel I keep rewriting, I too can test him: “You’re no longer a victim, Sam. And that means you have a new level of responsibility.” To figure out, now, what dent he wants to make in the world. He’s working on it, with a show on Instagram about autism and faith, with a book we’re working on about our ride together, with Facebook postings two or three times a week about the challenges he faces among neurotypicals. Sometimes that drifts into us against them, and it’s my point to Sam to get beyond that. That he must.

To which he says, “Do you think you’ll ever be done with your novel, Dad?”

I smile at that, and think, still amused, Goddamn wiseguy.

There's a place we all so desperately need to reach. If it seems that I’ve been led by my son to a deeper understanding not just of him but of myself, that’s exactly what opening my heart and mind to Sam, to his utter legitimacy as he is, commands. It is, of course, one of the oldest tenets of kindness: The more you give, the more you get back. And so it goes for understanding as well. The further we reach to understand the way another person feels the world, negotiates the world, becomes himself in the world—no matter what form that takes—the further we become open to ourselves. Because we must; I cannot touch Sam now without offering who I am, both to him and to myself.

I like those large thoughts, though not because they are profound; I like them because they are so simple. I have gone to Sam, and in doing so I’m gaining a bigger piece of myself, the guy who dived into work long ago as if that could make him whole.

“It means everything to me,” Sam said recently, “how you’ve opened up and allowed yourself to be vulnerable.”

My son, he didn’t have a choice with that. He has always been vulnerable. That’s what his autism gave him, and it’s now his gift to share.

esquire