There’s One President in American History Who Absolutely Did Not Want the Job. A New Show Reveals Why He Was Right to Be Worried.

This article contains spoilers for Death by Lightning.

Poor James Garfield. Although he is one of the four American presidents who were assassinated, he has never had so much as a commemorative airport or a tunnel, let alone a huge marble memorial (although his family home in Ohio is a national historic site and there are a boulevard and park in Chicago named after him). Instead, he is remembered, if at all, as one of the four “lost presidents”—Hayes, Garfield, Arthur, and Harrison—mid-to-late-19th-century figures notable for their imposing facial hair and substantial physiques, now largely relegated to the bottom half of the presidential league tables.

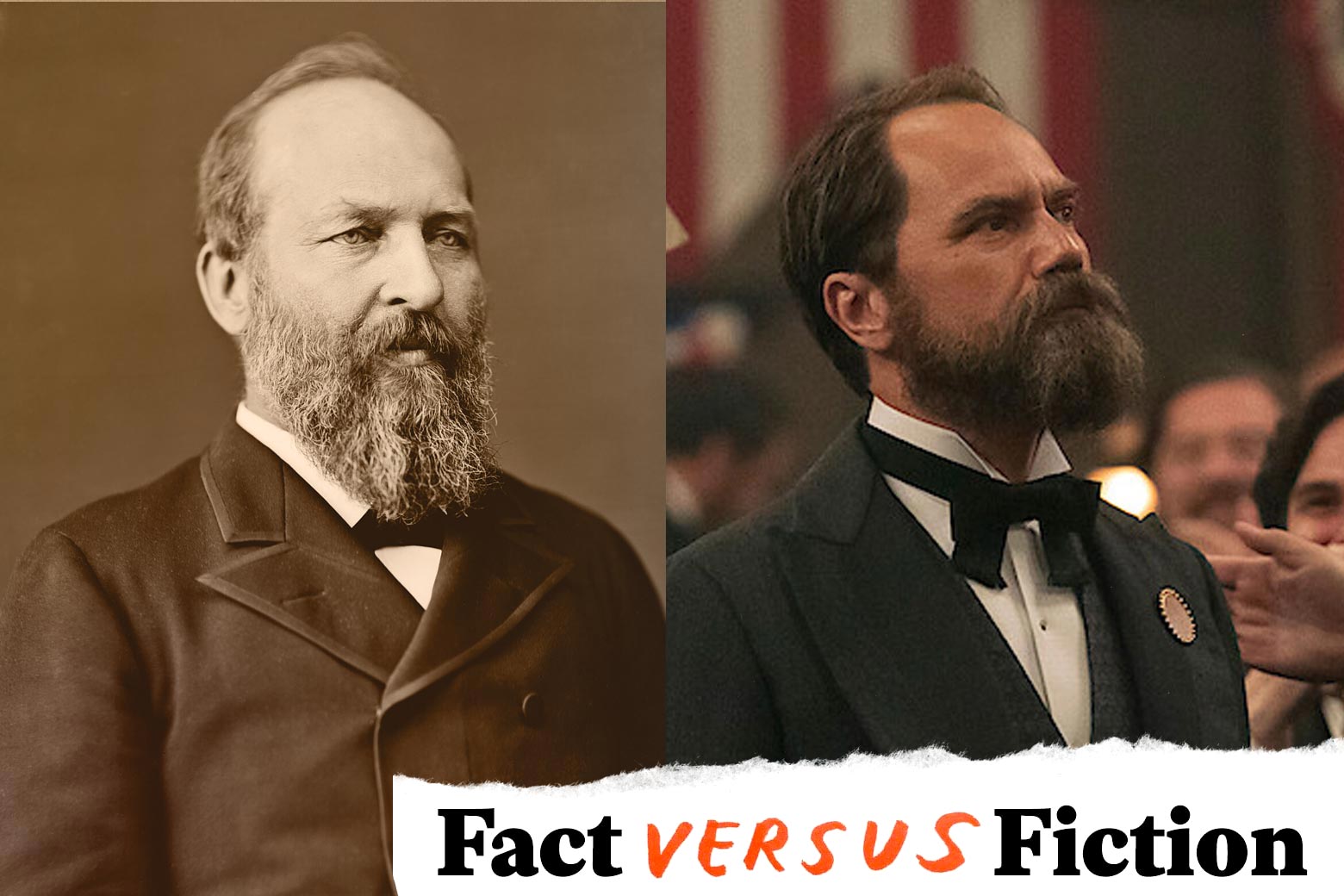

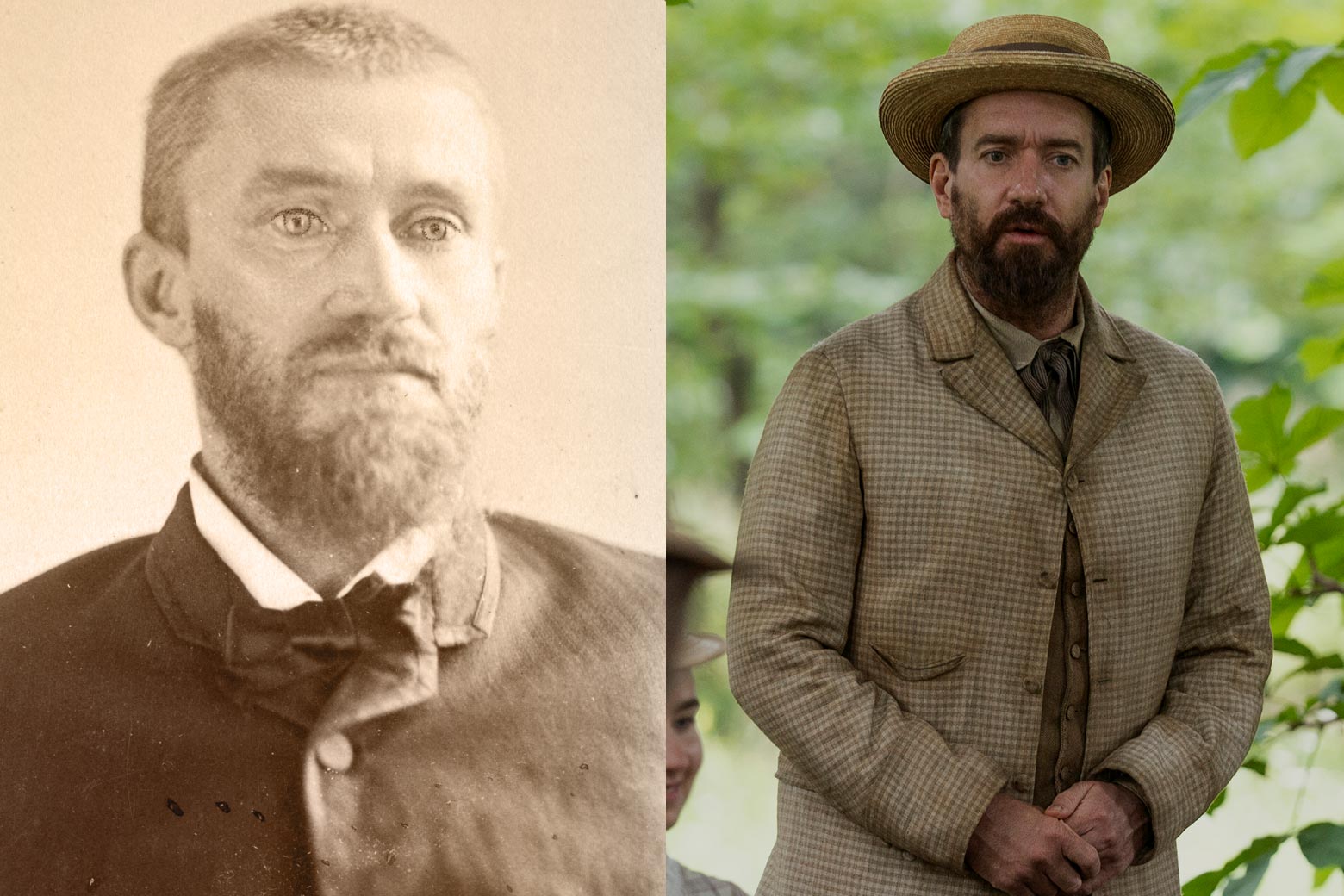

However, Death by Lightning (a reference to a glib assessment of a president’s chances of being assassinated) aims to pull Garfield (Michael Shannon) out of the historical shadows by recounting the events leading to and around his assassination in 1881 through the prism of a parallel biography of his killer, Charles Guiteau (rather like the 2007 film The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford). In his portrayal of Guiteau’s early days as a small-time chiseler and con man, Matthew Macfadyen makes him a more down-at-heel Tom Wambsgans, with the same combination of squirrely scheming and obsequiousness, before shading into a poignant portrait of a man bewildered by the increasing disconnect between his expectations and reality, as Guiteau descends further into mental illness.

What the series makes clear is that the divisions and repercussions of the Civil War persisted in the country like a low background hum for decades after the war itself was over, with almost everyone Garfield encounters either a veteran like himself or someone who has lost a family member in the war. And the issues the Civil War raised were still far from settled by the time Garfield took office 15 years later (indeed, some would argue are still far from settled). You might not think the internal politics of the Gilded Age Republican Party, the reform of the public service appointments system, and developments in late-19th-century medicine would provide fertile ground for drama, but somehow Death by Lightning pulls it off. Here, we look at if they manage it by sticking to the facts or by adding a dose of fiction.

The series presents Garfield as sort of a Midwestern Cincinnatus, the Roman general who gave up his appointment as dictator as soon as a state of emergency was over and retired to his farm (and whose followers, the Cincinnati, lend their name to a city in Garfield’s native Ohio). In other words, this Garfield is a pillar of modesty and rectitude who felt the call to public service but was much happier living quietly on the family farm.

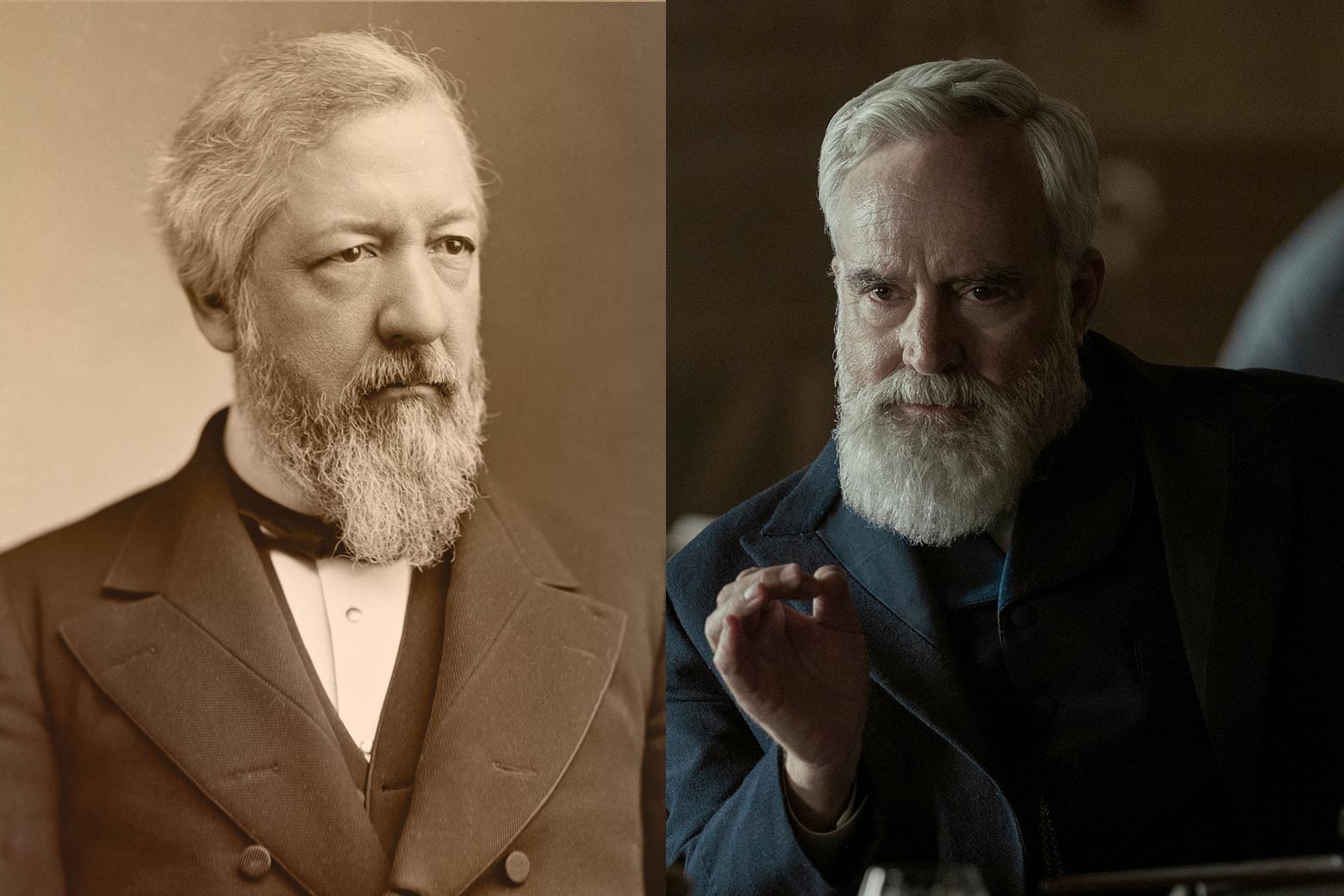

Over his wife Lucretia’s misgivings, he is lured to the 1880 Republican National Convention to nominate a fellow Ohioan, Sen. John Sherman. The convention is bitterly divided between the Stalwarts—the faction headed by party kingmaker Roscoe Conkling (Shea Whigham), so named because of their support for the spoils system, which awards high-paying government jobs as payment for party loyalty (and, as the senior senator from New York, Conkling controls many lucrative appointments)—and the Reform faction, which Sherman and Garfield belong to and which wants the civil service to be reformed and appointments made on the basis of merit.

Conkling gives a rousing speech to nominate the Stalwart candidate, former President Grant, but Garfield, who has been nervous about his address, outdoes him with a speech about the Republicans rededicating themselves to President Lincoln’s principles of emancipation (and which barely mentions Sherman), bringing the delegates to their feet.

Vote after vote leaves the convention deadlocked. On the 28th vote, there’s a lone voice for Garfield, who tells the nominator he doesn’t want the support. Even so, more and more delegates come into his camp, and on the 38th ballot he is nominated, much to his mortification, thanks to the machinations of Republican senator and power broker James G. Blaine (Bradley Whitford, cast once again as a political wheeler-dealer). He refuses to campaign beyond speaking to voters from the front porch of his Ohio farmhouse.

This is largely true—Garfield really didn’t want the job. When he heard from a friend that there was a move to introduce him as a candidate, he exclaimed, “My God … I know it, I know it! And they will ruin me!” A year before the convention, he confided to his journal that presidential fever was an “evil” that destroyed its possessor.

At the same time, Garfield was not quite a 19th-century Chance the Gardener, passive and clueless, although he did seem to have a talent for floating upward. Having already become America’s youngest brigadier general during the Civil War, a brave ride through enemy lines saw him promoted to major general. He was elected to Congress from Ohio despite never campaigning, with no less than President Lincoln persuading him to resign his commission and run as a Republican. He won reelection for 18 years and became House minority leader during the presidency of Rutherford B. Hayes, which suggests he wasn’t entirely a political naif. He clearly had political ambitions, just not presidential ones.

Unable to finish writing his nominating speech, Garfield goes out for a walk around his hotel. He encounters an elderly man who is clearly ill and, on discovering the man fought for the Union at some of the same battles as he did, invites him in for a drink. The vet says he has come to town for the convention but has nowhere to sleep because hotel rooms are so scarce. Garfield gives the man his bed and sleeps in a chair.

This is more or less true, although some details differ. The morning of his speech, a stranger knocked on Garfield’s hotel door and asked if he could sleep in Garfield’s bed with him as he was unable to find a hotel room. The kindly Garfield agreed, later writing to Lucretia (who he called “Crete”) that “the bed is only three-quarter size and with a stranger stretched along the wall, I could not get a minute of rest or sleep.”

After he wins the nomination, Garfield returns home to find a group of Black veterans protesting in front of his property. He invites them in, where they tell him there are obstacles like literacy tests being put in the way of their receiving voting rights, which Black soldiers were promised if they signed up to fight for the Union. Garfield promises to get rid of the literacy tests and any similar roadblocks to full voting rights.

In real life, Garfield was indeed a staunch supporter of equal voting rights (race-based; sex-based not so much). Both he and Conkling (who, whatever his ethical failings when it came to emoluments, had helped draft the 14th Amendment that extended citizenship and other legal protections to former slaves) robustly opposed slavery and advocated for the rights of formerly enslaved people.

As early as 1865, Garfield gave a speech in which he argued that the nation had made a promise to its Black soldiers, asserting that freedom was a “bitter mockery” if it merely meant not being chained and was not a “substantial, tangible reality” that included a person’s right to participate in government and their “opinion counted at what it is worth.”

Furthermore, in his inaugural address, he asserted, “The elevation of the negro race from slavery to the full rights of citizenship is the most important political change we have known since the adoption of the Constitution of 1787. No thoughtful man can fail to appreciate its beneficent effect upon our institutions and people … It has liberated the master as well as the slave from a relation which wronged and enfeebled both.” If he hadn’t been assassinated 200 days into his term, it is highly likely he would have worked to ensure equal voting rights.

However forward-thinking Garfield was on voting rights and cleaning up federal hiring corruption, when it came to labor rights, he was strictly a Midwestern conservative and budget hawk. He opposed various cooperative farm programs supported by beleaguered Western and Southern farmers who also backed legislation regulating railroads, calling them “communism in disguise.” He was against labor unions and believed federal troops should be used to break up strikes.

1878 finds the rootless Guiteau living in what appears to be the 19th-century equivalent of a hippie commune, where everyone produces and prepares the commune’s food and shares everything equally, including sexual partners. He spends five years there but never really fits in, accused by the others of taking more than his fair share. Even worse, despite the culture of free love, no one will get it on with him, and he’s known as “Charlie Get-out.” This just increases his determination to make his mark and become celebrated.

This is actually true. The Oneida Community, one of several small, experimental communities that sprang up in the 1840s founded on socialist principles, was a Christian millennial cult that lived communally and practiced what it called “Complex Marriage,” as its founder, John Noyes, believed monogamy was “unhealthy and pernicious.” In Complex Marriage, every man was married to every woman and vice versa. No attachment could be exclusive. In order to avoid an inordinate number of pregnancies, Noyes also advocated “male continence”—intercourse “up to the moment of emission,” or, as it was jokingly known as in the 20th century, “Catholic birth control.”

Even creepier was the practice of Ascending Fellowship, where certain members who were considered to be closer to God were allowed to choose a virgin partner who they would introduce via spiritual guidance to the principles of Complex Marriage. The principle of share and share alike extended to communal resources, with members dividing food and labor. Women were considered equal and shared in all activities.

Guiteau had difficulty following the rules. Members were expected to work in the fields and kitchens as needed, but Guiteau complained about doing menial work, considering it beneath him. Worse, the Oneida women rejected him, so he lived as a celibate in a free-love commune. After leaving Oneida in 1865, Guiteau was still sufficiently excited by Noyes’ ideas to spread them by founding a newspaper, the Daily Theocrat, to promote them. However, he became resentful at what he perceived as Noyes’ lack of recognition toward his contribution and initiated a lawsuit claiming compensation. He eventually dropped it, but continued to send threatening letters blaming the community for his personal troubles.

This was echoed in his relationship with Garfield, who he initially worshipped, offering his services to the campaign, only to later turn against the president-elect when it appeared his contribution was not properly appreciated.

On July 2, as President Garfield walks through Washington’s Baltimore and Potomac train station with Blaine (by now his secretary of state), Guiteau, believing himself to be acting on God’s orders, shoots him in the back. Charles Purvis (Shaun Parkes), a Black doctor from the nearby Freedman’s Hospital, starts to attend to the president and urges transferring him to the more sanitary confines of the hospital but is dismissed by the president’s official physician, Doctor Willard Bliss (his first name was actually “Doctor”). Bliss (Željko Ivanek) immediately starts rummaging around in Garfield’s wound using his unsterilized bare fingers and an equally unsterilized probe in search of the bullet, all without giving Garfield any pain relief, but to no avail. He orders Garfield to be put on a train to New Jersey where the first lady is at the seaside recovering from malaria. Garfield makes it to New Jersey, but over the course of the next three months deteriorates, finally dying in September.

This is true, although if anything Bliss’ care was even worse than shown in the series.Purvis did question Dr. Bliss about conducting an examination with unsterilized instruments and on the station floor even though it was unheard of for a Black doctor to challenge a white one at the time. Bliss had been expelled from the District of Columbia Medical Society due to an interest in homeopathy, and this might have explained his reluctance to adopt the newfangled germ theory of infection. Garfield was inclined to trust Bliss, a childhood friend from Ohio.

While Bliss declared the cause of death to be “blood poisoning from the bullet wound,” a coroner’s autopsy showed that Bliss’ probing had expanded a 3-inch entry wound into a pus-infected 21-inch wound track, resulting in Garfield’s death from sepsis. The bullet itself, safely encased in the abdomen and not touching any vital organs, would probably not have been a cause of death. This did not stop Bliss from presenting Congress with a $25,000 bill for his medical services.

Slate